Abstract

- Human is at the center of creation and usage of technologies;

- Human vulnerabilities account for 80% of total vulnerabilities exploited by attackers, yet the focus of cyber security is often targeted only on system tools and technology

- Attackers leverage Cognitive Bias, Defender struggle on them;

- Awareness and Engagement Campaigns used ill-adapted strategies and failed understanding of human psychology;

- Securing human’s digital use is a cross-disciplinary responsibility that need to be initiated and oversight by top management.

Introduction

When dealing with computer-related technologies, we tend to forget that the human is everywhere. It’s both the creator and the user. It is the salesman and the maintainer. In 1999, Bruce Schneier popularized the concept that cybersecurity is a combination of People, Process and Technology. Three years later, Kevin Mitnick states in his book “The Art of Deception: Controlling the Human Element of Security” that this very People component is the weakest in cybersecurity. Since then if Cybersecurity and Risk Management Frameworks flourished, if technologies expand and complexify, the People factor seemed to be stagnated. The most remarkable advancement being phishing simulation and boring awareness session. Not even speaking of mistakes and errors that cause incident and increase security risks. Is the user really the weakest link, or is it the understanding of human nature?

The “Weakest Link” status of technology user is not limited to security perception but extends to Software Development or IT support. Up to the point that it is caught into a meme known by every computer worker: the Problem Exists Between Keyboard And Chair (PEBKAC). Taking seriously this cartoonish interjection, it is an invitation to reframe the problematics from a pure Risk Mitigation perspective into an Ergonomics perspective. Instead of always put the blame on the end user, how can we design systems that engage them to behave on the intended way? How can we shape a Cybersecurity Strategy that encourage them to be an active part of the defence force? “Human Factor” in cybersecurity pops the idea of “User’s errors, mistakes, incompetence and innocence that sabotage my security efforts”. In Ergonomics it is defined as “the application of psychological and physiological principles to the engineering and design of products, processes, and systems.”. When stating that “the security problem is because of stupid user”, Security Managers and Specialists are acting in the same way of people arguing that “IT security is an IT matter”. Then, the PEBKAC is not at the user’s desk, but at security’s one.

The Double-Edge Sword Game of Influence and Behavior Change

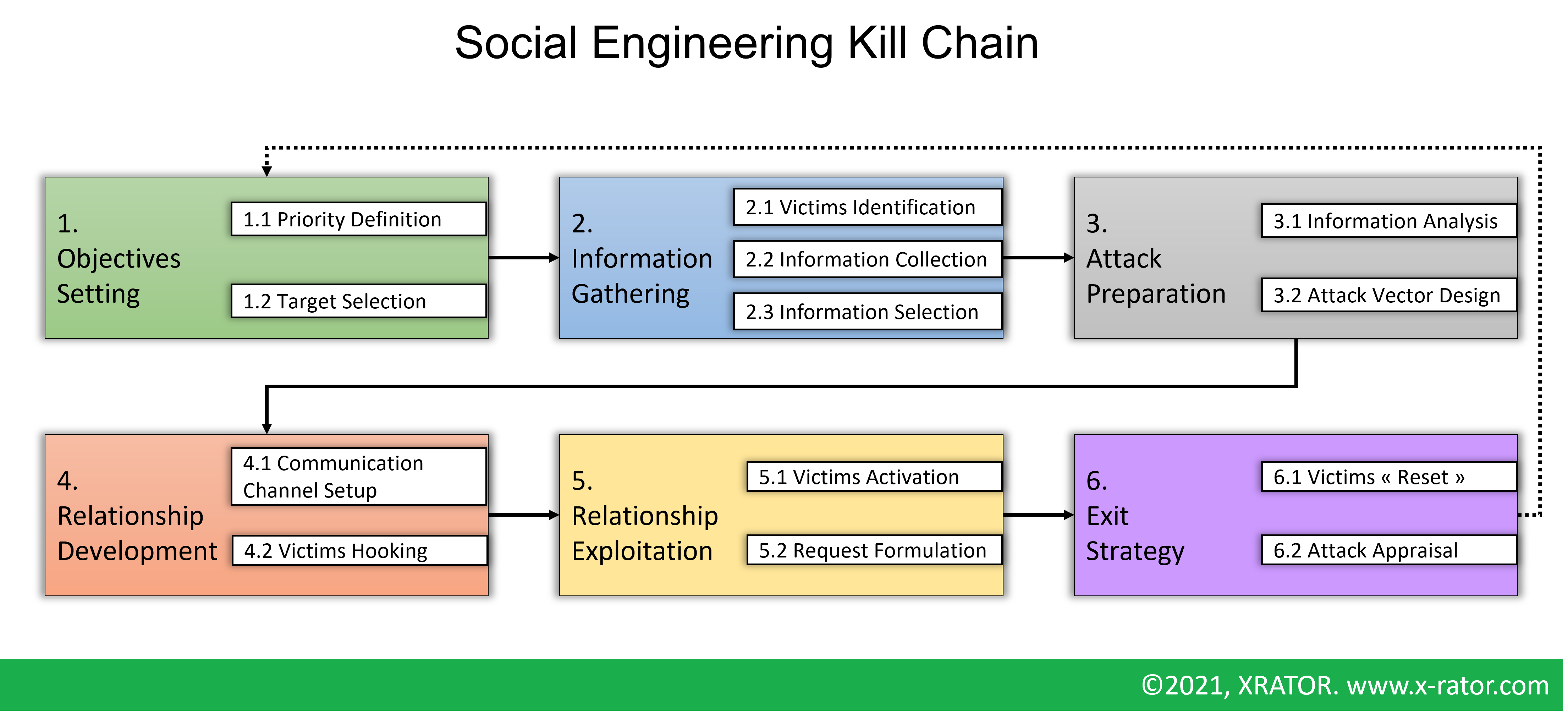

Attacker and Defender, when interacting with the People component both want the same thing: influence its behavior to perform the desired actions. Popularized in Computer Security by Kevin Mitnick, Social Engineering is one of the main tactics to perform a network breach. It can be leveraged for target reconnaissance by interacting with an employee to gather information, at the initial intrusion step by convincing a user to download a malware, at the exploitation step by tricking someone to install a malicious package or as a final actioner in financial cybercrime by transfer money into a criminal bank account. According to Verizon DBIR 2021, Social Engineering has been constantly ranking first or second Attack Pattern witnessed in network breaches since at least 2016. But social engineering is just the computerized version of the very old game of Psychological Manipulation that spies, or scam artists are playing since the age of times. According to Adam and Makramalla (2015) Human vulnerabilities account for 80% of total vulnerabilities exploited by attackers while the focus of cyber security is targeted on technology.

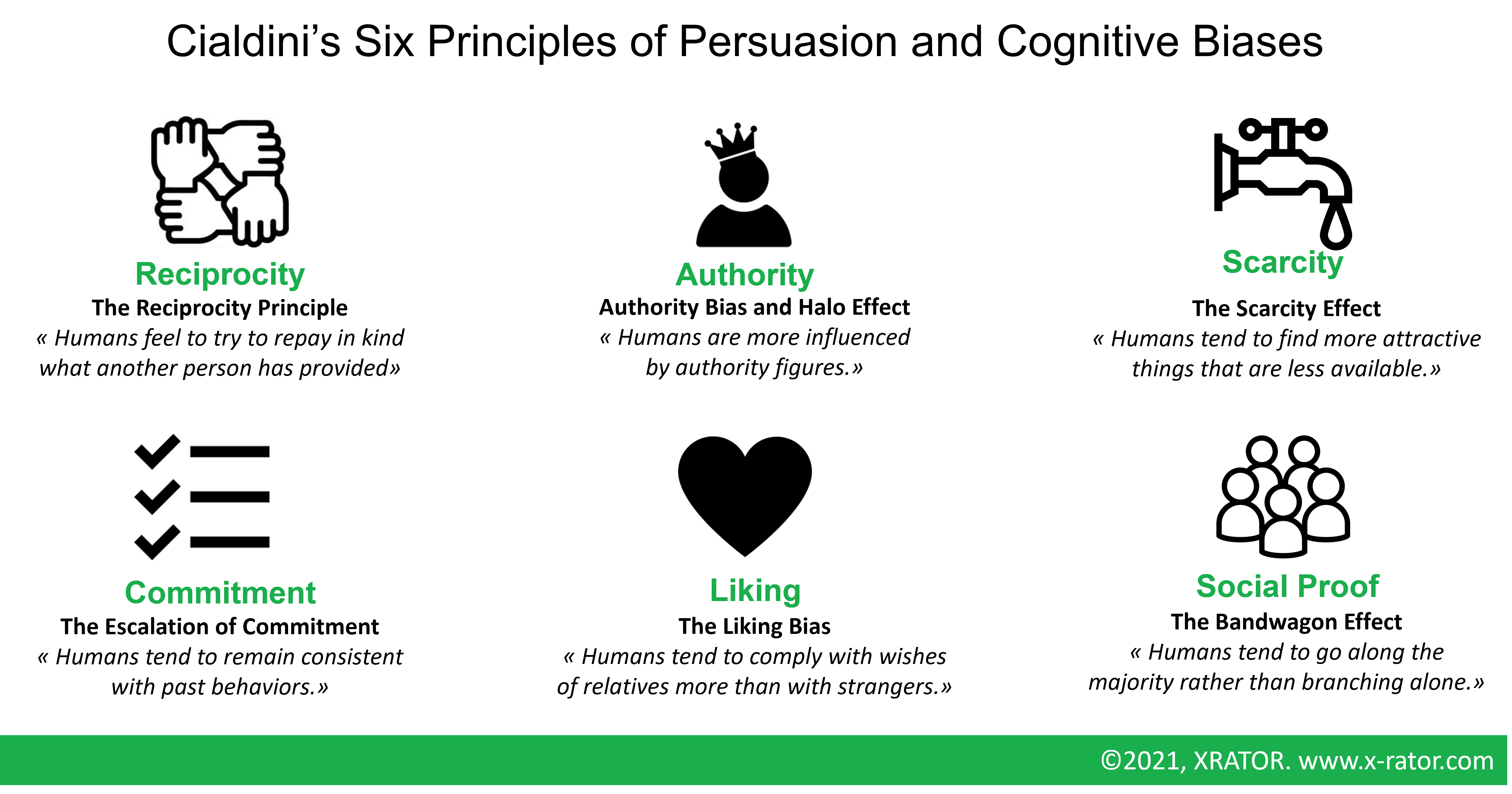

Spies, scammers, social engineers are leveraging Cognitive Biases, brain’s design features that impact an individual judgment, perception, interpretation and behavior. They are neither good nor bad, everyone is subject to it, creating a personal subjective reality. Those biases are extensively studied in behavioral economics, psychology, sociology, or neuroscience. They are leveraged everyday by advertisers, marketers, or politics to pass an idea to people that will turn into an action. Or by traders and financial specialists to avoid bad decision.

Where non-technical fields, or criminal, can deal with human cognitive bias, the cyber risk experts seemed to struggle with them or even running head down into them.

1. The Offensive Perspective: Cognitive Attacks and Human Characteristics Exploitation

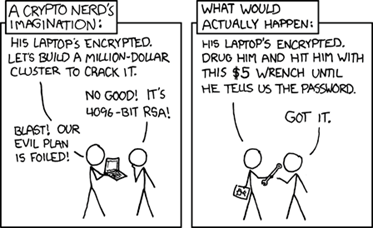

Social engineering is challenging the security of all networks regardless of the robustness of their firewalls, cryptography methods, intrusion detection systems, and anti-virus software systems. It enables the attackers to turn one of the security components (the “People”) into an unaware accomplice or insider threat. Even if each Social Engineering Attacks differs by means, tricks and objectives they tend to follow a “Research – Hook – Play – Exit” four phases structure.

We must not forget that all those attacks are performed at the end by a human being. But the entities that carry the attack are of two types: human-based and computer-based. In human-based attack vector, it is the attacker himself that interacts with the victims. In computer-based attack vector, the attacker crafts a digital content to indirectly interact with the target. In addition to the attack vector, three main information gathering tactics, and interactions tactics, can be identified:

- Technical-based: Social network, Digital Footprints, …

- Physical-based: Dumpster-diving, Habits Observation, …

- Social-based: Direct interaction with the target to play with its psychology and emotion

Then, the question of why an employee would engage in a behavior that go against its organization interest is very similar to why someone would agree to spy for a foreign country or why would someone try to fraud its company. A classical explanation of the drivers of such behavior is catch into the MICE acronym: Money, Ideology, Coercion, Ego. The underlying idea is that humans hold psychological vulnerabilities, and the exploitation of those vulnerabilities enable the manipulation process. This moralistic approach takes roots during World War 2, when the US Office of Strategic Studies (OSS) had to create a training cursus for the Secret Intelligence branch, with only 2 out of 50 blocks of instruction dedicated to spying agent recruitment, handling and communication. This very simplistic approach of motivation understanding is still widely used today.

In 1992, the United States Personnel Security Research Center (PERSEREC) published a quantitative survey of 117 individuals convicted or prosecuted for espionage. They added to MICE three new key motivations: Revenge, Ingratiation and Thrills. Welcome MICERIT. Another initiative, called Project SLAMMER, directly interviewed 30 spies to obtain a better understanding of psychology and surroundings. PERSEREC and Project SLAMMER were the first research trying to understand the psychology of espionage. But those works, and of course the underlying MICE, were imperfect. If in most case of espionage (and by extension Social Engineering) we can find one or more aspect of MICERIT, it also applies to a wide number of “honorable” people and profession. And moreover, it would imply that there are two kinds of people:

- Those who have a MICE property and can be manipulated or engage in fraud

- Those who don’t and should be immune to manipulation or criminal behavior

The reality is not that simple. Even between “good” and “bad” behavior, Professor Carson suggest in 1994 that “Espionage agent and heroic patriot may share the similar personal characteristics”. In 2013, CIA historian Randy Burkett offers an alternative framework inspired by social psychology and the “Six Principles of Persuasion” of social psychologist Robert Cialdini: Reciprocity, Authority, Scarcity, Commitment, Liking, Social Proof.

Cybercriminal, recruiting intelligence officer but also Internet Trolls or Clickbait Content Creator prompt activation of cognitive bias and exploit emotion center of their target. They focus on exploiting trust, joy, fear, or anger. Once experiencing these strong but basic emotions, the target’s body releases hormones and leads the logic center of the brain to shut down (Goleman, 1995). Amygdala hijacking is such an immediate and intense emotional reaction (Goleman, 2006). The release of serotonin or dopamine (related to happiness) may result in unpredictable action leading to an increased chance of social engineering (O’Neil, 2019). When experiencing fear or anxiety, the logic center of the brain shuts down while the emotional center of the brain is activated (Hadnagy, 2018).

Those social and psychological factors are well studied and known by scientists and academics. It is unlikely that cybercriminals spend hours to read academic literature to craft their social engineering materials, yet it does not prevent them to exploit with success those natural human tendencies. In the meantime, defenders design awareness campaign that may produce the opposite effect or generate a paralyzing and counterproductive Ostrich effect. Their perception of end users is also stuck between the PEBKAC and the MICE totems, making people needing to be “awaken” viewed as either stupid monkeys, flawed vulnerable individuals, or both.

Individuals who have a greater chance of falling into a social engineering trap are emotionally instable people (Kircanski et al., 2018), technology over-confident people or those who have the tendency to externalize blaming (Campbell, et al., 2004; Dutt et al., 2013; Farwell & Wohlwend-Lloyd, 1998). Victims may also develop psychosomatic and posttraumatic disease (Button et al., 2020; Leukfeldt, 2018). Cyberattacks and social engineering attacks don’t have impacts limited to digital or financial assets. A realized Cyber Risk may turn into a potential Health and Safety Risk.

Only a few victims seemed to show a positive change in response to a cyberattack, becoming « wiser » or « harder to hack » (Whitty and Buchanan, 2015). Then training, awareness and engagement campaigns are necessary in the defender strategy.

2.The Defensive Perspective: Secured-Minded Habits and Behaviors Adoption

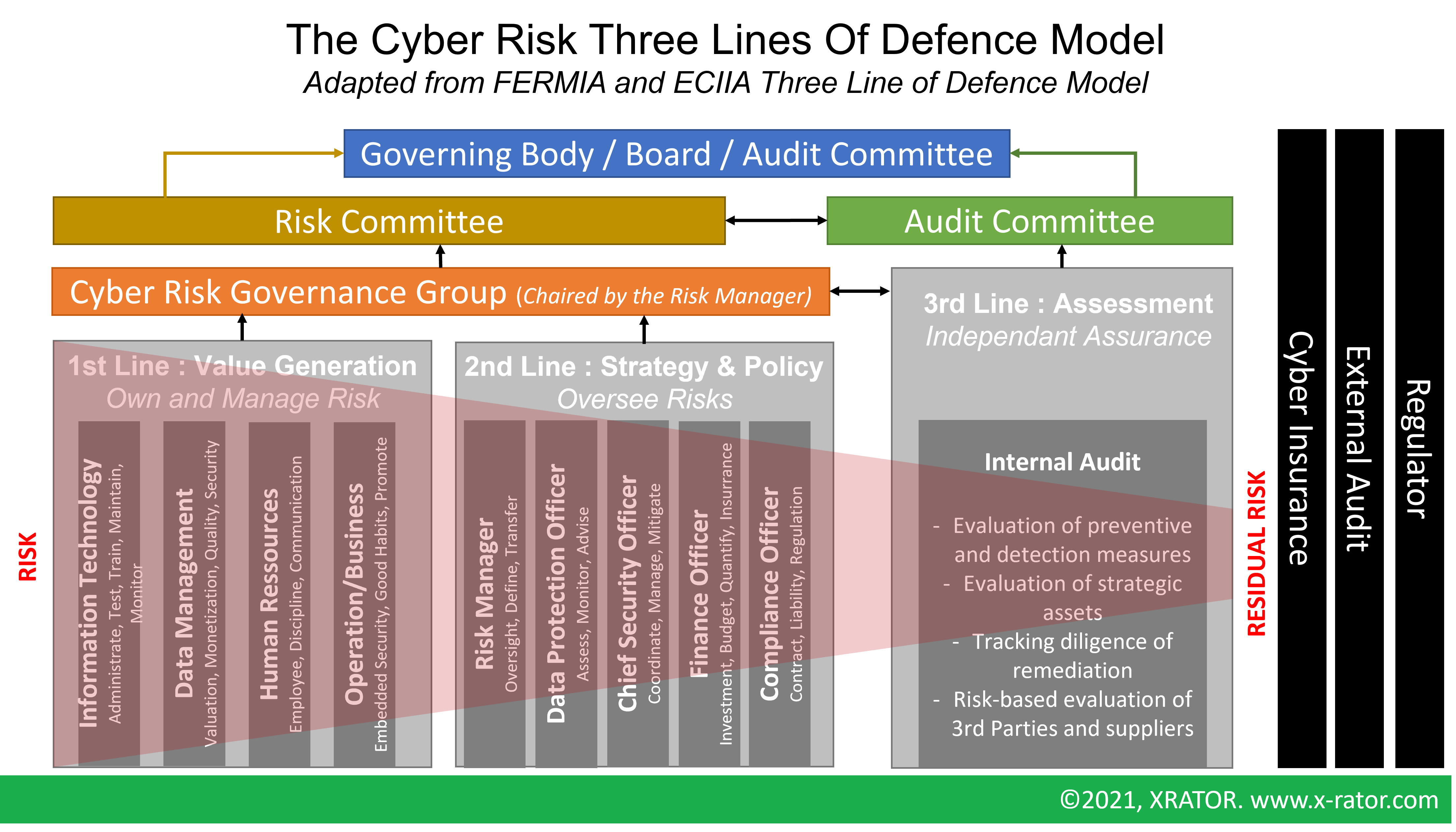

Organization may have several motivations to engage in a Cybersecurity program. But it seems generally more to comply with regulation and standard than knowingly protect them against their threats. The means are set as an objective. Hence, on the top of the cybersecurity activities food-chain lies the “Governance”. Process, policies, and control. Security by the textbook, this very textbook that attackers get around.

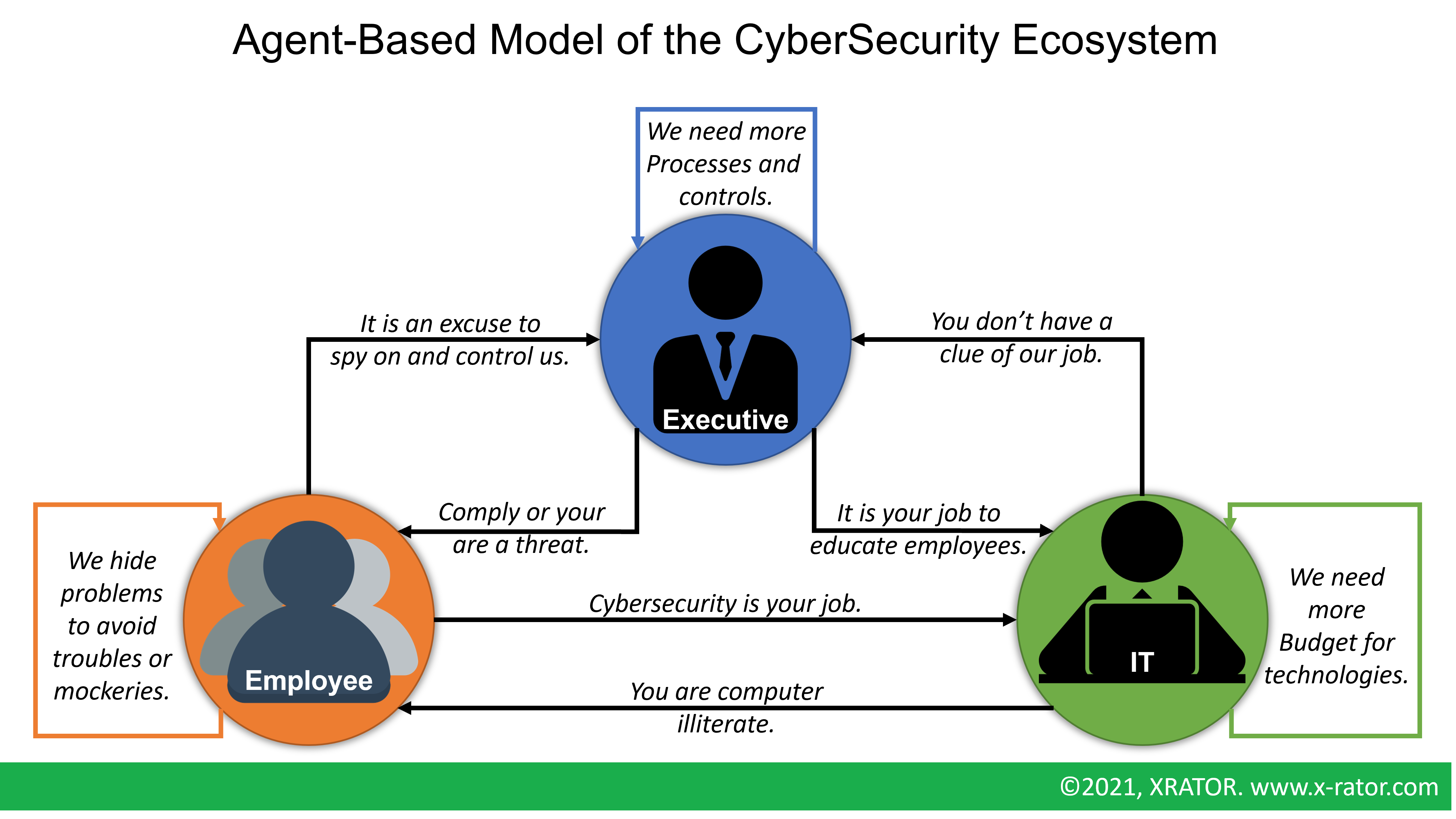

The objective is then not to be secure but to be compliant. An arbitrage is made between business objectives and security controls. Processes are designed. Technologies are purchased. Remain the users (“People”) that need to be “educated”. Awareness (behavior change objective) and Training (skills improvement objective) campaigns are then designed to steer the user’s behavior and skill toward the compliant way. There are not benefits for the user, it makes its jobs harder, they don’t understand the finality, they are incited by corporate punishments, motivated by fear. This shapes their whole perception of cybersecurity. We can model this social-technical relationship with an Agent-Based Model, drawing the dynamic, multi-actor, multi-objective and multi-level environment of the three decision-maker in Cybersecurity Programs: “executives”, “IT” and “regular employees”.

The problem for an organization’s executives or IT staff is that Individual Security Awareness Framework or Guidelines focus on the content and the business objectives, without taking account of people’s psychology. For Example, the SANS Security Awareness Maturity Model ™ describes five program levels:

- Nonexistent: no security awareness program

- Compliance focused: the program is designed to meet compliance, audit, and regulatory requirements

- Awareness & Behavior Change: the program matches people and topic to support the organization missions

- Culture Change: the program is part of the organization culture, is managed and updated

- Metrics Framework: the program has a metrics framework aligned with the organization’s mission to quantify and track progress and impacts

This is basically the application of the Capability Maturity Model (CMM) for Awareness Program, with a debatable order of the topics’ priority. In its 2021 Security Awareness Report, 53% of SANS survey respondents declared to stand at the Awareness and Behavior Change maturity level and 24% declared to be at the compliance-level. It seems that enabling an individual behavior’s change to the level of achieving a whole organization culture change acts as a bottleneck.

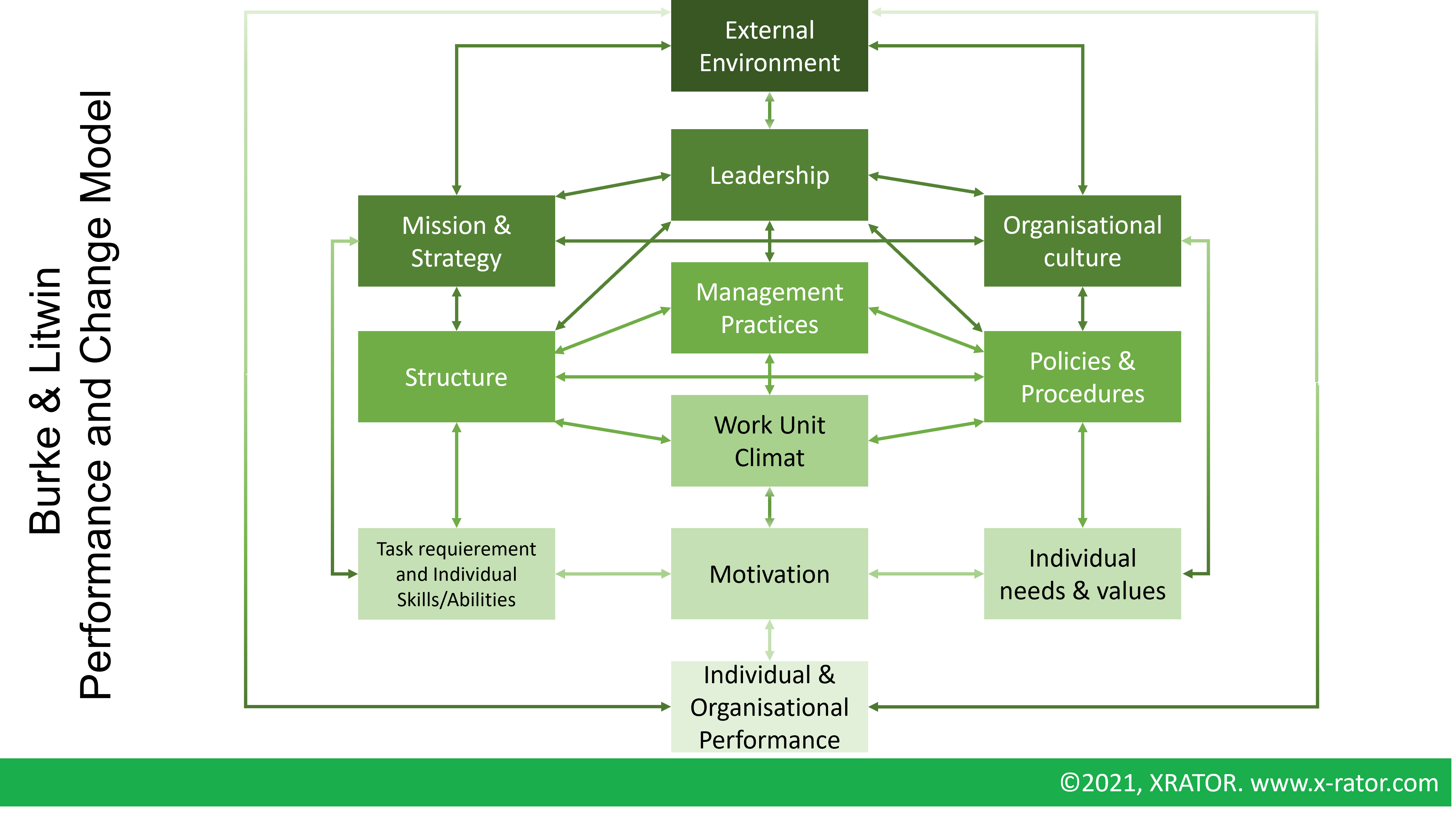

Any organization that starts or maintains an Awareness Program must make investment decision regarding security measures. Most of academic researches analyzing the IT-related security decision are quantitative, overlooking contextual factors such as behavior or environment (Heidt & Al., 2019). To take these drivers into account one can look the situation with the well-known Burke and Litwin Performance and Change Model. This is a general model describing the factors of change within an organization, summarized with bidirectional links between twelves mains factors. The most influential factors of change are at the top, and the least influential at the bottom.

The first lesson, applying the Burke and Litwin model to our topic, is that forging first an individual behavior change to then achieve a cultural change (as pictured in the SANS Security Awareness Maturity Model ™) is the hard-way solution. It seems easier for an organization, to first infuse the security matter into the organizational structure to then impact, at the very end, the employee behavior. The “Compliance, then Individual, then Culture, then Mission” awareness maturity path makes no sense according to Open Systems Theory.

The second lesson we can learn from the Burke and Litwin model is that the individual performance (the employee behavior fitting the security desired practice) is primarily influenced by External Environment and Employee motivation. The perception of the External Environment between the leadership (that impulses the Security Awareness) and the Employees (who adapt their working practice) may differ. For example, according to a defined risk landscape, the leadership may react on the market expectation, when Employees react on the regulatory aspects. The key challenge when setting up an Awareness program is then to identify the motivation factors of the Employees and to maintain this motivation level throughout a fast-evolving risk landscape.

Today’s main motivator for employees to change their behavior seems to focus on the fear factor. Either fearing the threat and its potential catastrophic consequences on the organization’s environment, either fearing internal negative outcomes on careers. If strong fear appeals have indeed a notable effect on the attitude (the feelings), it has more limited effects on the intention (behavioral potential) and behavior itself. Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) research even concluded that the threat focus can be misplaced. Instead, focusing on responding to the threat is more appealing to the employees. Those findings may be correlated with the Burke and Litwin model, where the Skills and Abilities of the Employee are a strong and direct influencer of the employee’s motivation.

This Burke and Litwin diagnosis of Awareness Program is very Top-Down, and other diagnosis methods could challenge these conclusions. But it acknowledges one practice currently used by organizations: the emphasis on Governance. If cybersecurity or cyberdefense operational units can help design material, it seems more effective to place Awareness at a strategic level, by-design aligned with the organization missions with a strong cultural and leadership support.

- Governance should work with leadership to build a clear mission statement for the organization regarding cybersecurity and integrate it in the organizational culture.

- Middle managers should attend the program among the first, with a particular focus on the compliance to Policies & Procedures.

- Employees’ awareness must focus on the practical skills they can incorporate in their daily routine.

- Management practices must incorporate the maintenance of the level of employee’s motivation towards secure working habits.

This is a radical change in the way we approach human security with awareness. Yet, it means an ability to break the Agent-Based Model described above, that executive embrace cybersecurity matters as a regular strategic and cultural topic, and that IT users stop being categorized as computer illiterates or pockets of vulnerability.

Three Advices for Engaging Employees into Security Initiatives

Drawing lessons from how attackers can manipulate IT users’ behaviors and what are the fundamentals of psychological and behavioral economics, we brought three mains advices to deal with the Human Factor that are designed to treat the following organizational challenges in cybersecurity:

- Underestimation of cyber threats and the probability to be attacked

- Underinvestment in time and budget in cybersecurity

- Discarding Cybersecurity as the sole job of the IT department

Those advices also aim to deal with the three mains factors leading individual decision-making to behave in an insecure way: failure to admit the risk or take responsibility for it by misplaced confidence, overstretched staff resources seeing cybersecurity as burdensome, and “social cyber-loafing” effect justifying and even protecting carelessness cyber behavior.

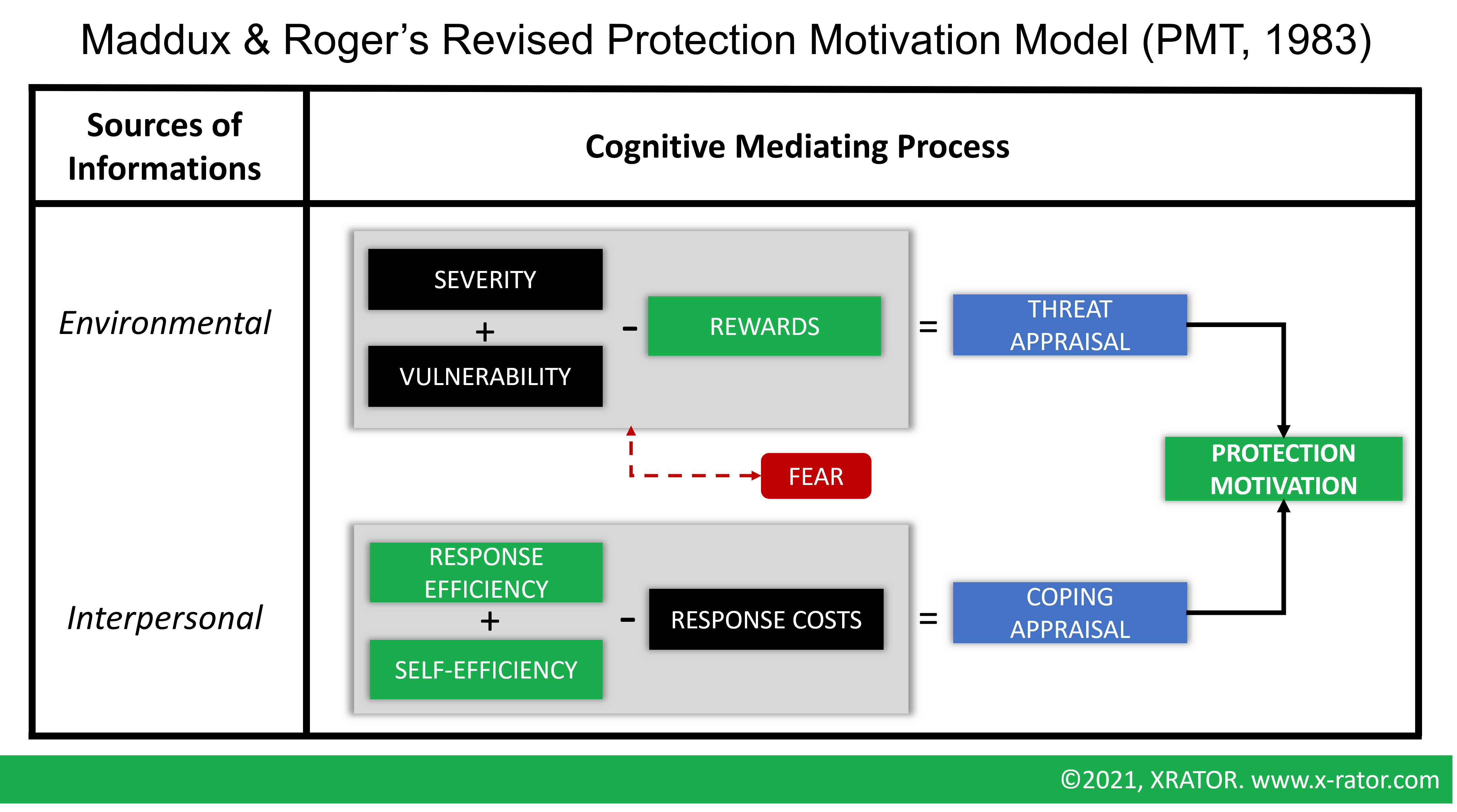

1. Facilitating instead of Scaring

We have previously seen that the main factor leading an employee to change its behavior toward a secure use of technology lays in its motivation. We have also seen that if threat-based messages may be eye-openers (high impact on attitude), they have a lower impact on behavior. To understand the motivators, we can rely on the Protection Motivation Theory (PMT). PMT is a behavioral theory that aims to identify the elements that a decision-maker relies on to whether protect itself or not against a threat, and which is widely used in cybersecurity (Rogers, 1983; Floyd et al., 2000).

The Threat Appraisal (Severity + Vulnerability – Reward) assesses the danger and seriousness of a situation in the eye of an individual:

- Severity refers to the perception of harm a threat can do;

- Vulnerability refers to the perceived probability to experience harm;

- Rewards refers to the benefits of ignoring the threat.

The coping appraisal (Response efficiency + self-efficiency – response costs) assesses the response by an individual:

- Response efficiency refers to the perceived effectiveness of the recommended behavior in removing or preventing possible harm;

- Self-efficiency refers to the belief that one can successfully enact the recommended behavior;

- Response costs are the perceived costs associated with the recommended behavior.

The right dose of fear, or threat-based messages, encourages individuals to take protective measure or refrain from actions that might harm themselves or other. It gives environmental information that are not yet enough to build motivation and turn into actionable protection measures. But too much fear, or threat-based messages, will shut down the logic center of the brain and encourage emotional response.

The impediments of cyber protection motivation, impacting the perceived response efficiency and perceived response costs, are quite often:

- No added value in their own task;

- Low risk probability perception of being attacked;

- Overconfidence in the current security measures;

- Risk transfer to contractors or IT specialists;

- Risk responsibility transfer to contractors or IT specialists.

On the other side, a driver of cyber protection motivation is financial benefits. For example, if an employee’s payroll is indexed to the performed tasks per day, and that skipping the security verification has no financial repercussion, she or he will happily skip this part of the process to increase its daily task counter. Another driver is the quick and visible effect of a security concern handover. If employees report a spam message but continue receiving the same, they will stop engaging. Or if employees report a phishing attempt to only received a “we have well received your report”, they will stop engaging too. Reporting, quickly and visibly on the impact of their action is crucial.

Rewards are a key incentive for behavior change. An Awareness Security Program should then be incorporated in a greater organizational strategy, with some key focus:

- Indexing every Middle Manager bonuses on security KPI;

- Engaging employee in vigilance and reporting with rewarding outcomes like bonus or “Cyber Security Champion of the month”;

- Limiting threat-based awareness messages to the amount of information necessary to evaluate a situation dangerousness;

- Emphases action-based awareness messages that give accessible ways to respond to cyber risks;

- Chasing in process situation where engaging in unsecure behavior is beneficial.

Finally, in addition with the above, IT and Software specialists must design tools both for employees to engage in the cybersecurity process, and tools that by design reduce the envy and the probability of dangerous behavior.

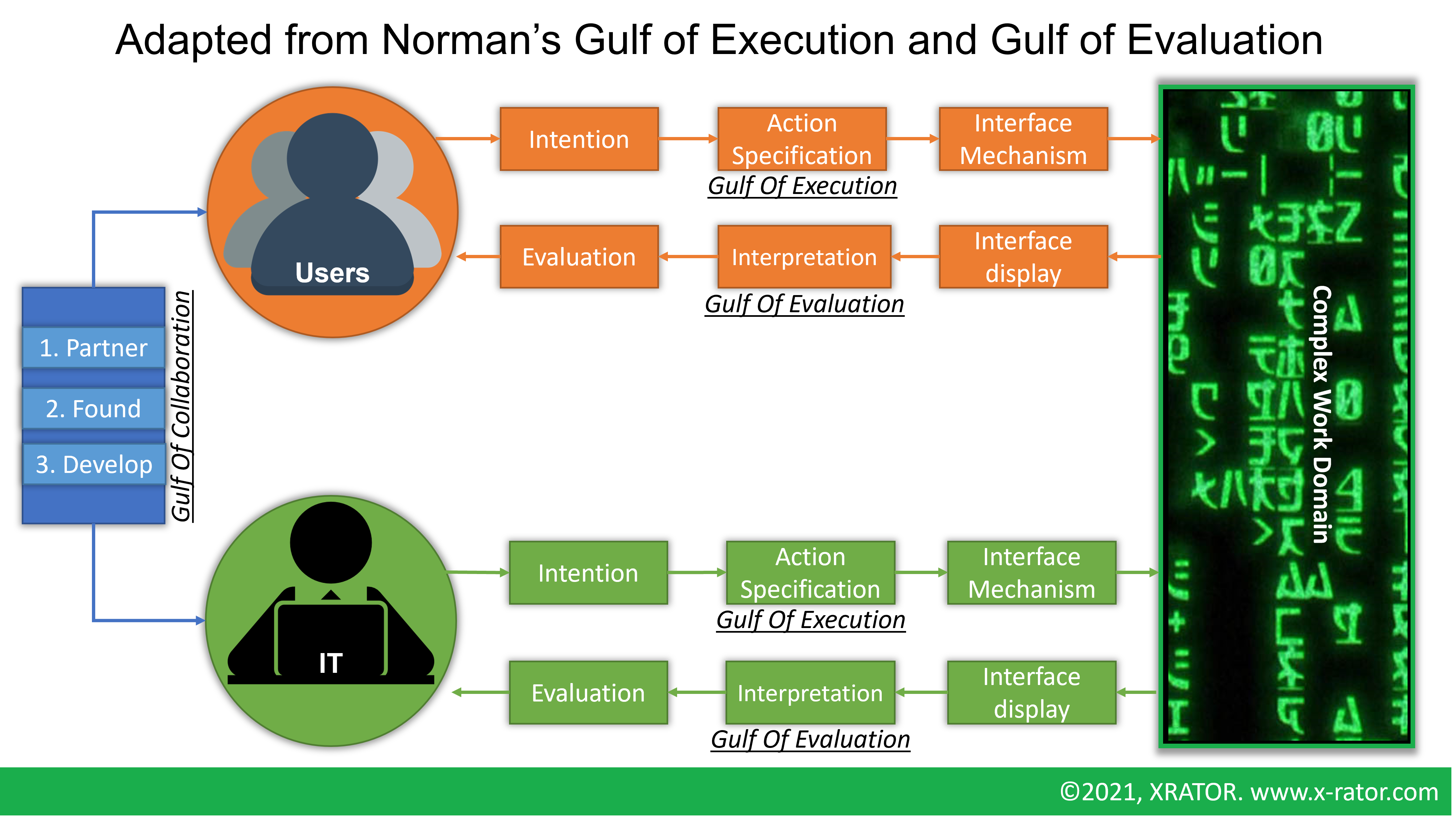

2.Ergonomics as part of Security-by-Design

Directly related to the Awareness and Engagement Program we discussed earlier, ergonomics can help build tools and software, to the employee audience, that:

- by design reduce the perceived response costs with intuitiveness and role-based approach;

- enhance the perception of self-efficiency with intuitiveness and gamification;

- improve the speed and the visibility of the global security efforts with appealing reporting to promote response efficiency;

- create a shared social norm regarding secure habits.

But as the Awareness and Engagement Initiative, ergonomics deals with the “Employee/User” agent. As seen with our Agent-Based Model of the Cybersecurity Ecosystem, we must also deal with the IT to User relation.

All security incidents or warnings are not coming from external intentional threats. They may be prompted by users’ mistakes or errors. The source of a mistake is generally an incident, an unintentional wrongdoing that was allowed by the system. The source of an error is a lack of knowledge of skill.

IT projects and Software deployment projects that impact the operations of users generally, or should, have a change management plan. This is a first step where ergonomic security applies, ensuring that users have been provided the right knowledge and the right training to reduce the error rate. Of course, IT people will not be the right people for training an accountant with a new accounting software, but the deployment project management must include this training. And the CISO or the Security Supervisor must have in its project security checks on this aspect of the deployment. This very basic principle is one of the easiest and most profitable to implement, as training an employee to a new software has a direct impact on its performance, hence has added value. For organizations that already have a change management process, this may be just an additional check box in a security checklist. For those who don’t, this is an activity that has a direct beneficial impact on the staff performance while increasing cybersecurity.

Security Supervisors should also care about the software’s usability by the targeted audience. Poorly designed softwares, error rate put aside, may leads to two situations that is increasing security risk:

- Cyber fatigue, misuse of the system and compensatory actions (Galitz, 1993) that may reduce the overall trust of digital technologies and reduce the PMT’s coping appraisal

- System Abandonment (Hiltz, 1984; Galitz, 1993) that creates technological graveyard

On the other hand, a well-designed software interface has sizeable impact on learning time, performance speed, error rates and user satisfaction (Schneiderman, 1992). Taking care of the software usability by the users and be sure that the interface is well-designed are again tasks that decrease cybersecurity risks with direct positive impact on the business performance.

Reducing the users’ mistakes, the accidental wrongdoing, is achieved by designing software that enforces a strong control of user input. This is of course a standard rule of software programming, as would Eugene Spafford, Computer Science Professor at Purdue University say: “A secure system is one that does what it is designed for”.

Security-by-design is not limited to software development but embraces the whole technological project scope. The strict enforcement of acceptable user interactions with a system is of course easier to implement for an 100% in-house production. Most people will engage in reducing procedural and design flaws if they are introduced to it in a valuable way. An aware and motivated business line will create by-design secured business requirements. And IT to deliver security features should be turned into competitive advantage and leverage the customer-centric Digital Transformation trend to market security and privacy for any type of business.

For external solutions deployment, an organization can take additional measures to shield the system, but it would be way more efficient that the software provider corrects them into the core. The organization can, at the negotiation level with the provider, ask their lawyer to review the contract. If there are no specification regarding security responsibility or update, the lawyer could suggest additional clauses to contractualize changes to the software for security measures. Or the Purchasing Manager could integrate in the prospected solution benchmark the security, the maintainability, and the usability criteria. This is where we understand that other specialties provide expertise that can be very beneficial for the organization’s cybersecurity.

3. Design a cyberdefense strategy including every employee

The common perspective of cyber security is that it is a cost center, a business blocker, a technical matter. Cybersecurity specialists must decrease this perception by not jumping first with more draconian security measures or more training for technical people. Top priorities are to build and maintain Business Security Guilds and create consistent procedures.

As we have seen with the Burke and Litwin model, in line with the common sense, needless to say that without the support of the highest ranked executive, it will be difficult to convince other stakeholders of the seriousness of the approach. In our Agent-Based Model, this mean working on the Executive to IT and Executive to Employee relationship. Executives must integrate security in their Mission & Strategy and infuse it into the organizational culture to have meaningful and seamless positive impacts.

Cybersecurity specialists can also create bridges with “Brothers and Sisters in Arms”, those corporate functions that are also perceived as cost centers, business blockers, and technical matters:

- Compliance;

- Legal;

- Quality;

- Human Resources;

- Accounting;

- Audit.

These functions work to a similar global end. Establishing a productive working relationship with those will give more weight to engage in security measures. Industry regulations are a base for the security baseline, and adhering to security standards can only please internal audit. Continuous training plan build with HR expertise, to increase the level of cyber security readiness, have also impact on the employees performance, fulfillment and may reduce the turn-over of scares ressources.

One last thing that Cybersecurity Teams can do to ease the integration of security into projects is to create dedicated practical processes and guidelines, that fit into the culture and the structure of the organization. A process gives consistency, predictability, and readability to Business Unit Project Managers, and give repeatable methods for auditors. Once the Embedded Security Process is defined and validated by high-ranking executives, it can be injected into the regular project management process of the organization.

Executives must understand that now cybersecurity is a matter of corporate governance. It goes beyond the implementation of security measures and the strict adherence to cybersecurity standards, that are just a kick-start minimal baseline to address the most common risks. For executives to know with accuracy the level of exposure to cyber threats, the organization must leverage all its workforce, from finance to business operations. This cross-disciplinary approach is believed to become a standard, that is relevant for both big corporation and Small & Medium Enterprises.

Conclusion

In universities and engineering schools, IT specialists learn that information technologies are based on physics and mathematics. They view computer networks and applications as a deterministic and predictable environment. So, when things get wrong the natural conclusion is that it is because of a disturbing factor, as known as, the user. This is where lies, or should lie, the fundamental difference between an IT specialist (that focus on the cyberspace’s logical layer) and a cyber specialist (that must deal with physical, logical and social layers). When a cyber specialist sees the user as part of the system to secure, the IT specialist see the user as a threat to the logical system.

If IT and Cybersecurity specialists are given a genuine responsibility in the management of employee behavior with technology, starting with executives, and that it is perceived as a profitable cyber readiness opportunity instead of a costly and annoying security rampart, then this is the most effective way.

Dealing with the Human Factor in cybersecurity is generally equating to create and maintain an Individual Security Awareness Program. We have seen that the Human Factor is deeper than that. It is not enough to throw information at employees. Ergonomics of tools and softwares, focusing on security reflex building, rewarding good practices, using fear-appeal and threat-based messages with parsimony, organizing cross-disciplinary committees, and foremost executive engagement in integrating security in the Mission & Strategy and culture of the organization have a greater impact than the common Awareness practice.

Moreover, we highlight that current Security Awareness, that is just one aspect of Human Factor Security, takes the wrong road by starting with Compliance, then Behavior, then Culture, then Strategy & Mission. We also highlight that the main factor in behavioral change is led by the employee motivation and perception of its ability to produce an appropriate response to a threat.

The relationship between human and technology is a corporate governance matter before a technical one.

Reference

- Bruce Schneier, People, Process and Technology. January 2013.

- MITNICK, Kevin D. et SIMON, William L. The art of deception: Controlling the human element of security. John Wiley & Sons, 2003.

- LEE, John D., WICKENS, Christopher D., LIU, Yili, et al. Designing for people: An introduction to human factors engineering. CreateSpace, 2017.

- WIELE, Johannes. Pebkac revisited–Psychological and Mental Obstacles in the Way of Effective Awareness Campaigns. In : ISSE 2011 Securing Electronic Business Processes. Vieweg+ Teubner Verlag, 2012. p. 88-97.

- Verizon, Data Breach Investigation Report 2021. Last consultation : 2021-08-30.

- HASELTON, Martie G., NETTLE, Daniel, et MURRAY, Damian R. The evolution of cognitive bias. The handbook of evolutionary psychology, 2015, p. 1-20.

- SALAHDINE, Fatima et KAABOUCH, Naima. Social engineering attacks: A survey. Future Internet, 2019, vol. 11, no 4, p. 89.

- CHARNEY, David L. et IRVIN, John A. The Psychology of Espionage. Intelligencer: Journal of US Intelligence Studies, 2016, vol. 22, p. 71-77.

- WOOD, Suzanne et WISKOFF, Martin F. American Who Spied against Their Country Since World War 2. DEFENSE PERSONNEL SECURITY RESEARCH CENTER MONTEREY CA, 1992.

- Central Intelligence Agency, Project SLAMMER Interim Report. April 1990.

- EOYANG, Carson. Models of espionage. Citizen espionage: Studies in trust and betrayal, 1994, p. 69-91.

- BURKETT, Randy. An alternative framework for agent recruitment: from MICE to RASCLS. Studies in Intelligence, 2013, vol. 57, no 1, p. 7-17.

- CIALDINI, Robert B. Influence et manipulation. First, 2012.

- BUTTAN, Divya. Hacking the Human Brain: Impact of Cybercriminals Evoking Emotion for Financial Profit. 2020. Doctoral Thesis. Utica College.

- VAN DAM, Koen H., NIKOLIC, Igor, et LUKSZO, Zofia (ed.). Agent-based modelling of socio-technical systems. Springer Science & Business Media, 2012.

- HUMPHREY, Watts S. Characterizing the software process: a maturity framework. IEEE software, 1988, vol. 5, no 2, p. 73-79.

- BURKE, W. Warner et LITWIN, George H. A causal model of organizational performance and change. Journal of management, 1992, vol. 18, no 3, p. 523-545.

- JANSEN, Jurjen et VAN SCHAIK, Paul. The design and evaluation of a theory-based intervention to promote security behaviour against phishing. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 2019, vol. 123, p. 40-55.

- WARKENTIN, Merrill, WALDEN, Eric, JOHNSTON, Allen C., et al.Neural correlates of protection motivation for secure IT behaviors: An fMRI examination. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 2016, vol. 17, no 3, p. 1.

- STAFFORD, Tom. On cybersecurity loafing and cybercomplacency. ACM SIGMIS Database: The DATABASE for Advances in Information Systems, 2017, vol. 48, no 3, p. 8-10.

- MADDUX, James E. et ROGERS, Ronald W. Protection motivation and self-efficacy: A revised theory of fear appeals and attitude change. Journal of experimental social psychology, 1983, vol. 19, no 5, p. 469-479.

- FLOYD, Donna L., PRENTICE‐DUNN, Steven, et ROGERS, Ronald W. A meta‐analysis of research on protection motivation theory. Journal of applied social psychology, 2000, vol. 30, no 2, p. 407-429.

- GROBLER, Marthie, GAIRE, Raj, et NEPAL, Surya. User, usage and usability: Redefining human centric cyber security. Frontiers in big Data, 2021, vol. 4.

- FERMIA/ECIIA Joint Expert Group, At the junction of corporate governance and cyber security. September 2017.