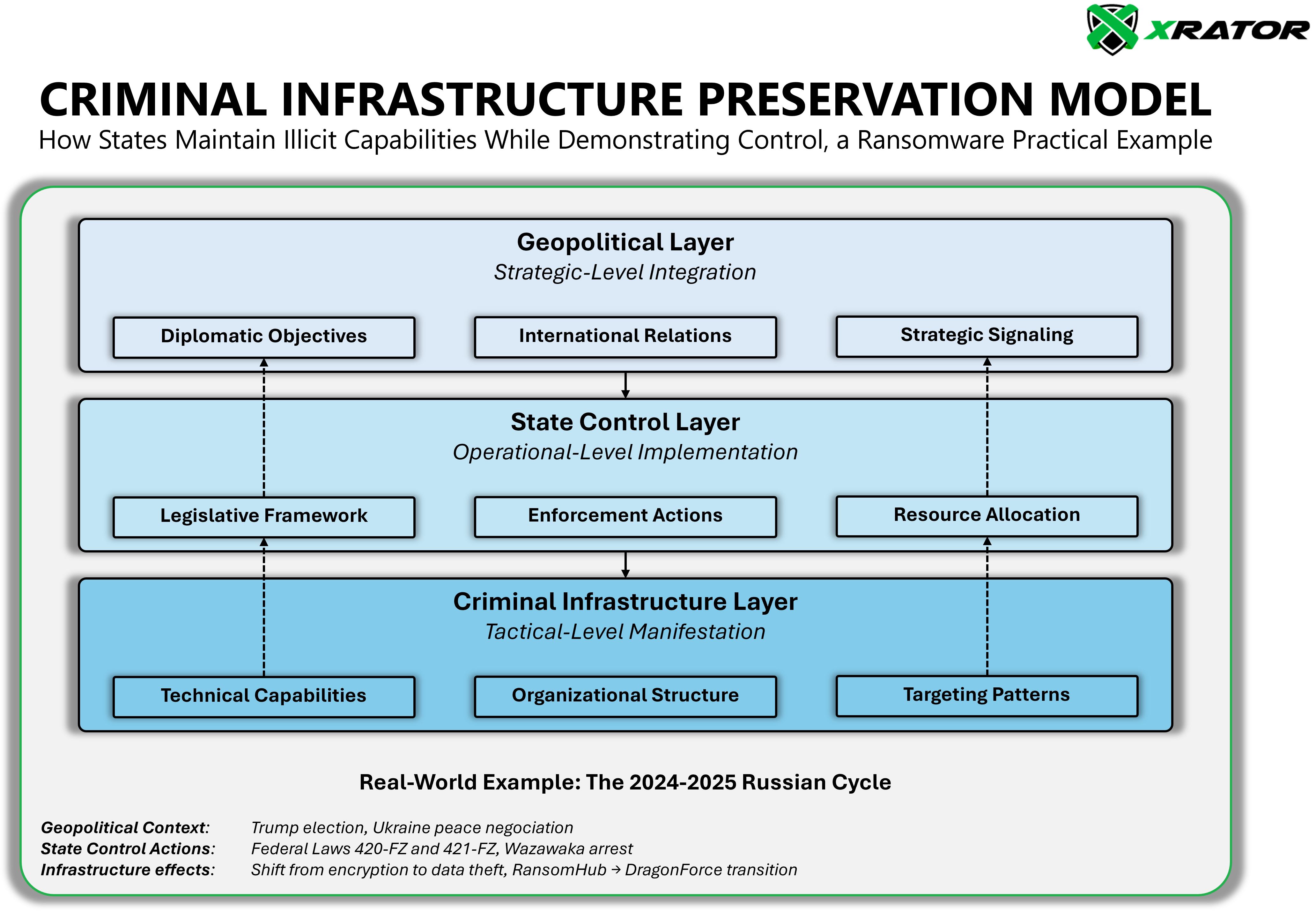

Recently, observers of the cybercrime landscape have been puzzled by dissonant patterns that only make sense when viewed through the lens of what we call the Criminal Infrastructure Preservation Model (CIPM), applied to ransomware.

At the intersection of cybercrime and geopolitics, a counterintuitive dynamic has emerged that defies conventional cybercrime analysis. While analysts focus on ransomware’s statistical contradictions (record-high attacks despite declining profits) they may miss the strategic logic beneath: states aren’t eliminating criminal infrastructure during crackdowns, they’re demonstrating control while deliberately preserving it.

These aren’t contradictory indicators of a failing criminal enterprise but

coherent signals of a criminal ecosystem operating under strategic direction.

Ronan Mouchoux, XRATOR‘s CTO

The Sovereignty of Persistent Criminal Infrastructure

When Mikhail “Wazawaka” Matveev was arrested by Russian authorities in November 2024, cybersecurity analysts celebrated another blow against ransomware. This individual was presented as a key figure of the russian cybercrime ecosystem, suspected to have ties with proeminent underground forum (RAMP, XSS) and ransomware gangs (Babuk, Lockbit, Conti). A doubtfull perspective according to insiders. And within weeks, new groups like Arkana Security, Secp0, and Skira Team emerged with sophisticated capabilities, targeting critical infrastructure with remarkable precision. This wasn’t coincidence but consequence.

As Agamben’s “State of Exception” theory (State of Exception, 2005) would predict, authorities periodically suspend normal legal orders not to eliminate threats but to demonstrate sovereignty over them. Ransomware groups become homo sacer – entities legally “killable” yet preserved as strategic assets. The apparent crackdown transforms into a ritual of sovereignty that reinforces state power while maintaining valuable clandestine capabilities.

The conventional narrative suggests these new groups represent the resilience of criminal markets. When one criminal falls, others rise to take their place. But this explanation collapses when we examine the technical sophistication of these “new” groups. As Rapid7 researchers discovered when comparing Babuk’s and CyberVolk code, these aren’t novel creations but redeployments of existing infrastructure with key modifications.

What we’re witnessing isn’t the natural evolution of criminal markets, but the controlled reallocation of criminal resources under state supervision.

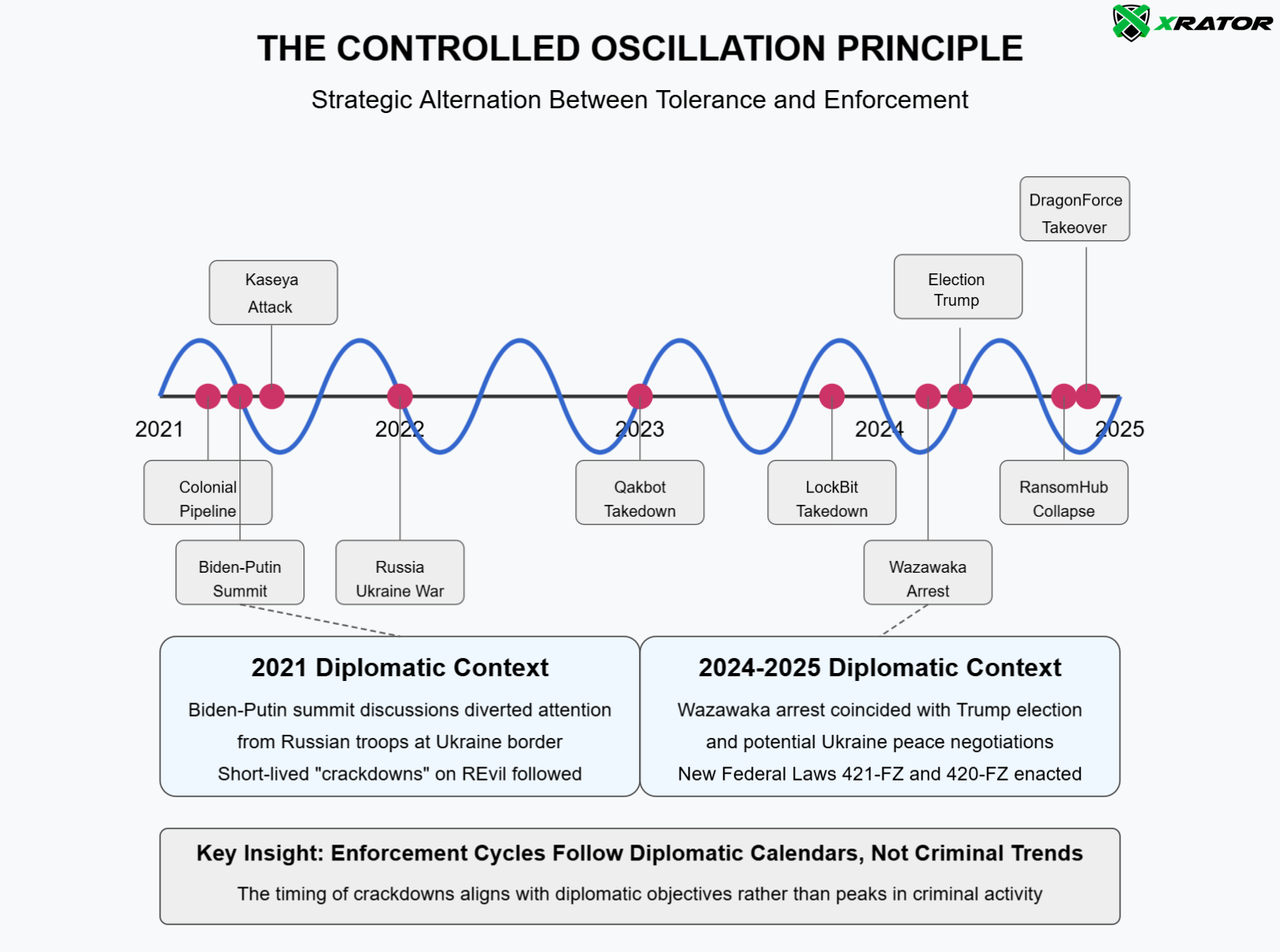

The Controlled Oscillation Principle: Strategic Rhythm of Law Enforcement

A foundational principle within the Criminal Infrastructure Preservation Model is the Controlled Oscillation between tolerance and enforcement.

Between October and December 2024, Russian authorities detained “hundreds of people” on cybercrime and money laundering charges. This dramatic wave of enforcement coincided precisely with Trump’s election victory (november 2024) and emerging Ukraine peace negotiations seeing USA siding with Russia, revealing the strategic utility of crackdown. This wasn’t Russia’s first cybercriminal “arrestation wave,” but part of a pattern established in earlier episodes.

Bittner’s concept of “Street Sovereignty” (The Functions of the Police in Modern Society, 1970) illuminates this dynamic. Just as police demonstrate authority through selective enforcement in physical spaces, states maintain “digital precincts” where their writ runs unchallenged. New groups emerge not despite crackdowns but because of them – sovereigns replacing unruly lieutenants with more compliant proxies.

Consider the sequence of events:

- May 2021: Colonial Pipeline attack disrupts U.S. East Coast fuel supplies

- June 2021: Biden-Putin summit where ransomware is a central topic

- July 2021: REvil conducts Kaseya supply chain attack affecting 1,500+ businesses

- October-December 2024: Wave of Russian cybercriminal arrests coincides with Trump election

- January 2025: Record-breaking 92 disclosed ransomware attacks reported

- February 2025: Attack surge reaches 956 victims globally

- March 2025: RansomHub (largest group) goes offline, DragonForce claims takeover

This oscillation between tolerance and enforcement follows a strategic rhythm aligned with diplomatic calendars – a pattern introduced by Putnam’s Two-Level Games theory (Diplomacy and Domestic Politics: The Logic of Two-Level Games, 1988), where domestic actions serve international negotiation purposes.

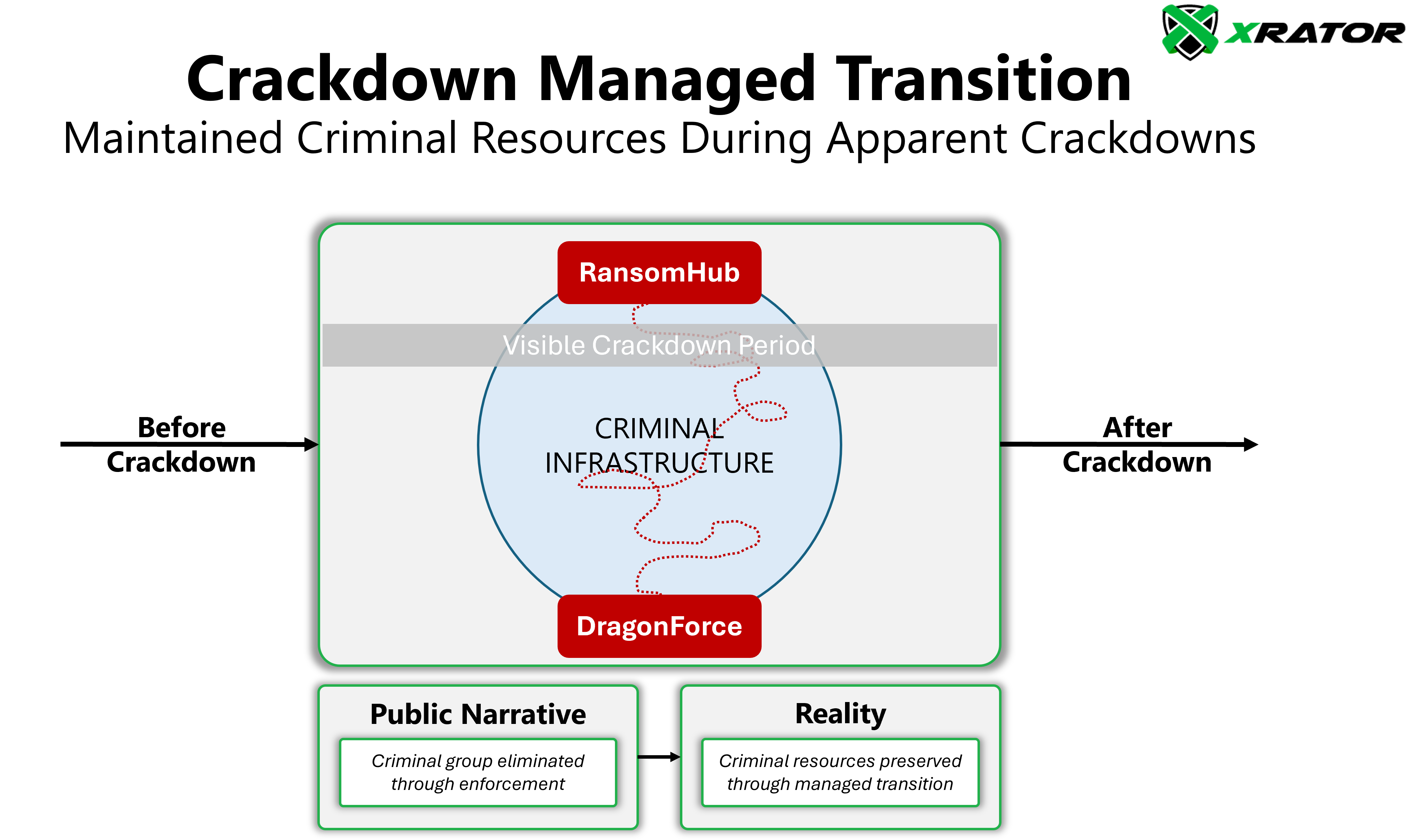

Criminal Infrastructure Preservation Through Managed Transitions

The second principle of the Criminal Infrastructure Preservation Model is the Crackdown Managed Transition, where critical criminal resources are maintained during apparent crackdown.

The most revealing pattern emerges when we examine what happens between crackdowns. The rapid emergence of new groups with sophisticated capabilities suggests not spontaneous market evolution but managed transition of resources.

Consider the strange case of RansomHub’s collapse in March 2025. When its data leak site went offline, DragonForce (a Lockbit and Conti fork) quickly claimed to have taken over its infrastructure while promising a “white-label approach” that would allow affiliates to develop their own brands.

The technical sophistication of this transition, wich maintain operational capability while changing visible leadership, aligns precisely with Pfeffer & Salancik ‘s Resource Dependency Theory (The External Control of Organizations: A Resource Dependence Perspective, 1978), where organizations ensure continuous access to critical resources even during apparent restructuring.

This preservation serves multiple strategic purposes:

- Maintaining Technical Expertise: Sophisticated hacking capabilities require continuous development

- Operational Continuity: Preserving access to compromised networks and systems

- Intelligence Collection: Maintaining visibility into criminal operations provides valuable insights

- Strategic Reserve: Preserving capabilities for potential future deployment

The corporate crime calculus (Decision making Models and the Control of Corporate Crime, Yale Law Journal, 1976) provides another explanatory framework: states manage criminal ecosystems through controlled liability, targeting mid-tier operatives while preserving core infrastructure, just as corporations might sacrifice division heads while protecting institutional knowledge.

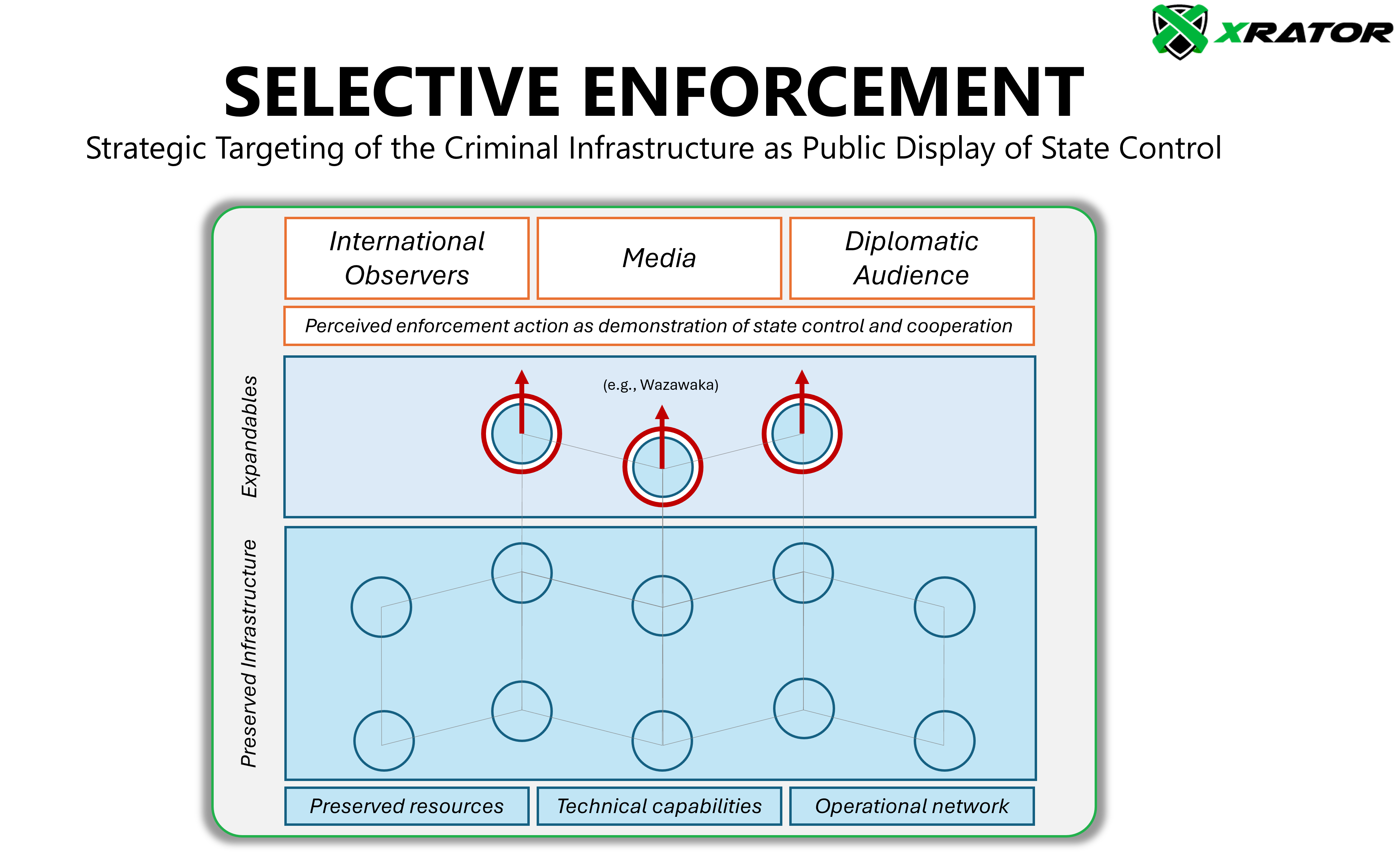

Sovereign Demonstration Through Selective Enforcement

The third principle of the Criminal Infrastructure Preservation Model is the Selective Enforcement. Symbolic actions are used to demonstrate the dominance of those in power. An existing concept that can be summarised as “for friends, everything; for others, the law“.

When an anonymous hacker told Russian newspaper Gazeta.ru that “Russian security forces do not like chatterbox hackers who attract a lot of attention in the West” and described Wazawaka’s arrest as “a warning,” they revealed the central mechanism of power projection: selective enforcement as demonstration of state control.

The November 2024 Federal Laws (No. 421-FZ and No. 420-FZ) serve a similar function. These laws don’t attempt to eliminate cybercrime but formalize the state’s authority over it. It creates a legal framework that allows for precise, targeted enforcement when strategically valuable.

This selective enforcement serves as public demonstration of sovereignty. What Foucault’s Governmentality central concept (Security, territory and population, 1978) describes as power exercised through visible displays of authority. Aligned with Putnam’s Two-Level Games theory, It signals to both domestic and international audiences that the state maintains control over activities within its digital borders, even when it chooses not to exercise that control.

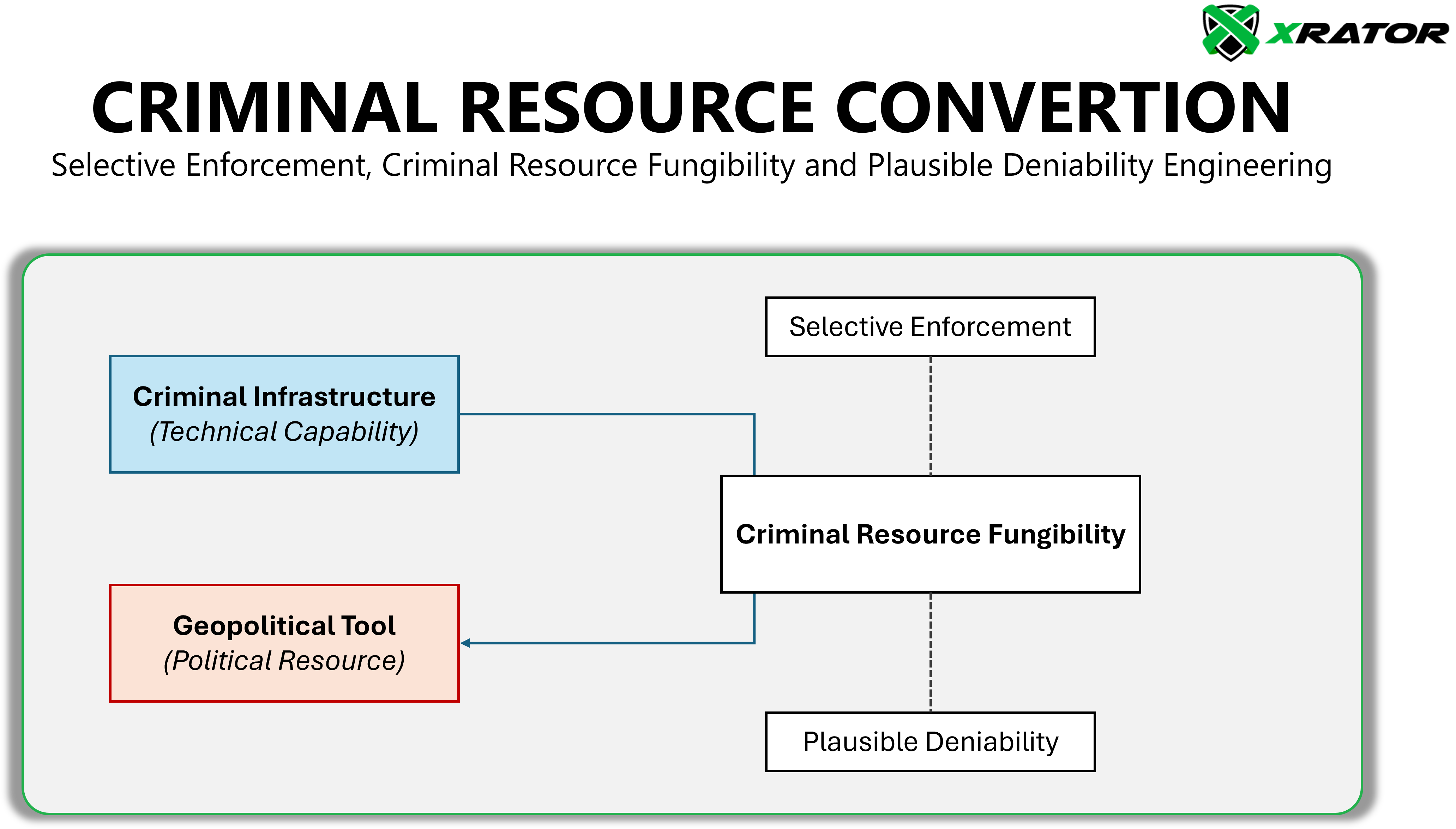

Criminal Resource Fungibility: Criminal Infrastructure as Sovereign Capital

The fourth principle of the Criminal Infrastructure Preservation Model is the Criminal Resource Fungibility: the context-specific conversion of criminal infrastructure into diplomatic leverage.

While David A. Baldwin’s critique of power fungibility (Power Analysis and World Politics, 1979) rejects the notion of easily interchangeable resources across domains, his framework permits tactical repurposing when three conditions align:

Domain congruence: Criminal methods (e.g., ransomware) match the target state’s vulnerabilities (e.g., digital dependency).

Controlled application: States limit conversions to scenarios where criminal tools outperform conventional options (e.g., deniable coercion via hacker proxies).

Recipient susceptibility: Adversaries perceive criminal-derived threats as credible (e.g., Western democracies prioritizing critical infrastructure protection).

Baldwin’s anti-fungibility thesis thus paradoxically validates this principle: precisely because power resources resist broad interchangeability, states exploit criminal niche advantages where traditional tools (military, intelligence, economic) are politically costly or ineffective.

Russia’s 2021–2025 ransomware diplomacy demonstrates how cryptocrime infrastructure, while non-fungible for territorial defense, becomes potent in gray-zone confrontational domain requiring plausible deniability.

This explains the otherwise puzzling metrics observed in early 2025: record-high attack volumes (demonstrating capability) coupled with declining profits (reflecting operational constraints). These aren’t contradictory indicators of a failing criminal enterprise but coherent signals of a criminal ecosystem operating under strategic direction.

The geographic pattern of attacks reveals this strategic orientation. According to the cybersecurity firm Cyble, as U.S.-targeted attacks dropped from 67% of global ransomware in February to 52% in March 2025, we see not random market forces but deliberate redirection. The surprising surge in attacks on German targets (from 22 to 40 in a single month) similarly reflects strategic reorientation rather than chance.

These shifts allow states to demonstrate control while preserving capabilities. It shows they can direct criminal infrastructure away from politically sensitive targets while maintaining operational capacity for future leverage.

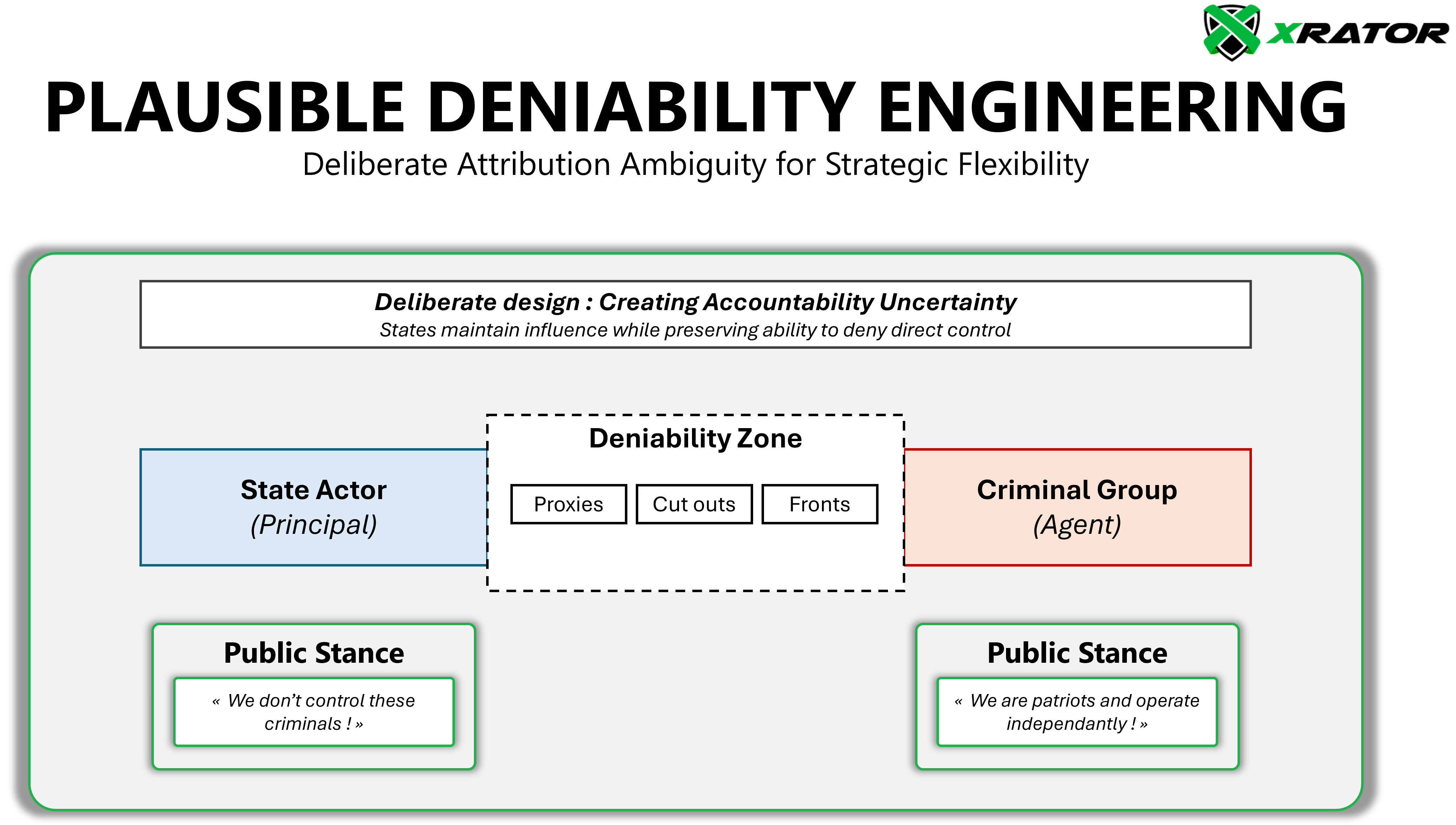

Plausible Deniability Engineering: The Value of Ambiguity

The fifth principle of the Criminal Infrastructure Preservation Model is Plausible Deniability Engineering. It involves the deliberate creation of accountability ambiguity. This isn’t a byproduct of cybercriminal tradecraft but a strategic design element. Plausible Deniability Engineering serves Schelling’s Coercion Framework (Arms and Influence, 1966) core purpose: maximizing coercive power while minimizing escalation risks. This is ambiguity serving as strategic leverage.

Principal-Agent Theory (Jensen & Meckling, Theory of the Firm, 1976) provides a framework for understanding this dynamic: states maintain strategic information asymmetry with criminal groups, allowing them to disavow specific actions while maintaining overall direction. This creates what the Gazeta.ru’s anonymous hacker described as one of the bargaining chips in emerging diplomatic relations.

The power to hurt is bargaining power only if it is not used.

Schelling, Arms and Influence, 1966

The technical evidence for this engineered deniability appears in the rapid rebranding cycles. When DarkSide rebranded as BlackMatter after the Colonial Pipeline attack, they preserved the codebase while resetting public attribution. Similarly, when Babuk emerged using LockBit 3.0’s source code or Russian GRU’s “Sandworm” group sharing tools with cybercriminals, they weren’t simply recycling available tools or services but deliberately creating accountability confusion.

This pattern of preserved capability under new branding serves both criminal and state interests. Criminals escape immediate heat while states maintain strategic ambiguity about their relationship to specific actors.

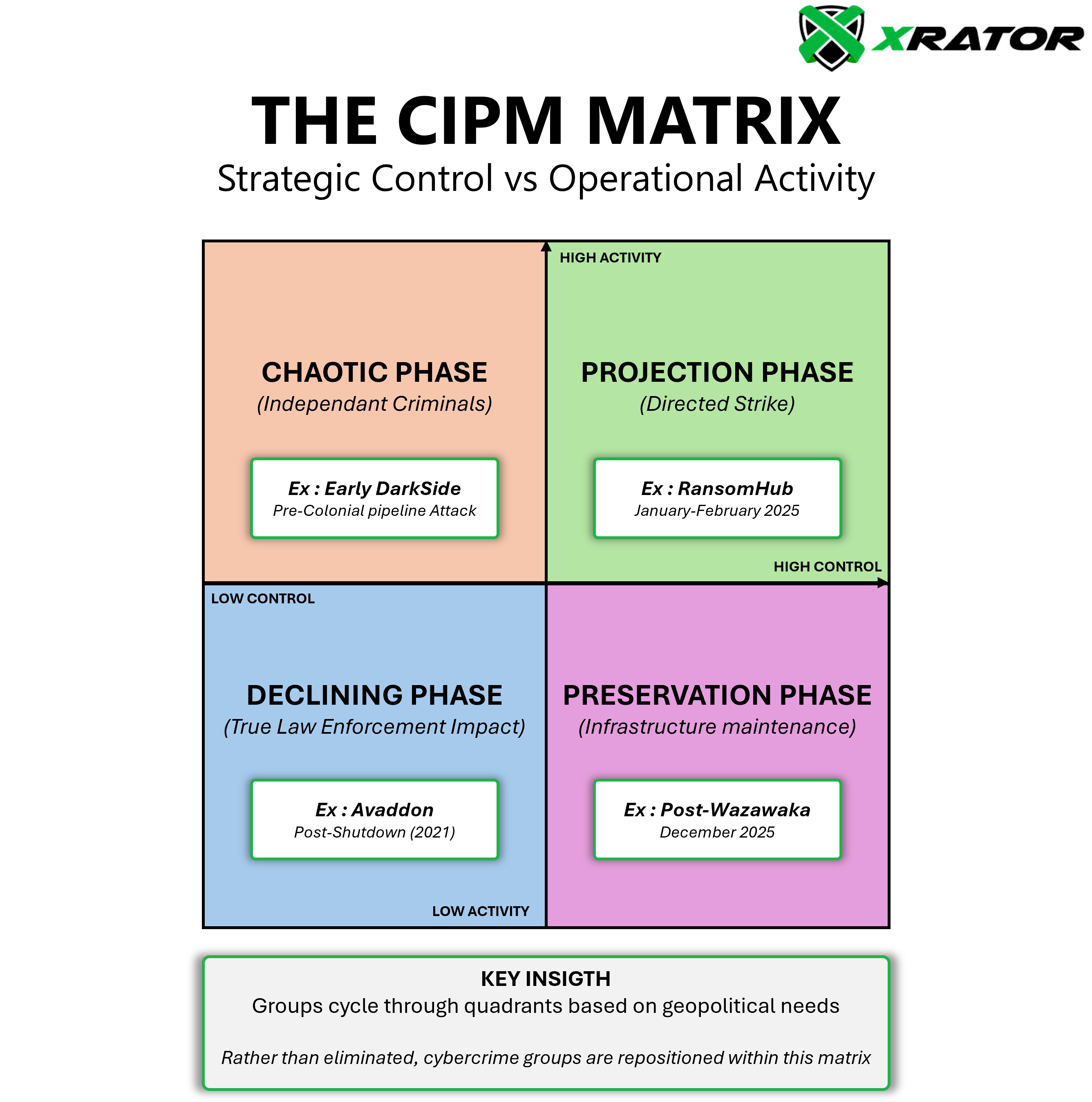

The CIPM Quadrant: Understanding Strategic Positioning

The relationship between state control and operational activity creates a dynamic matrix that explains the seemingly chaotic patterns in ransomware activity:

- Projection Phase: High activity with high state control (strategic deployment)

- Preservation Phase: Low activity with high state control (infrastructure preservation)

- Chaotic Actors: High activity with low state control (independent criminals)

- Declining Market: Low activity with low state control (true enforcement impact)

Groups cycle through these quadrants based on strategic needs, with states managing this positioning to serve diplomatic objectives. When Russia sought to signal cooperation following Trump’s election, it moved groups from the Projection to the Preservation phase through selective arrests. Similarly, the surge in attacks in early 2025 represents a controlled movement back toward Projection as diplomatic conditions evolved.

This matrix explains why traditional analyical lens fail to make sense of current events. Groups aren’t eliminated but repositioned within this matrix according to geopolitical needs.

Beyond Russia’s Cybercrime: A Global Phenomenon

While Russia provides the clearest example of Criminal Infrastructure Preservation, this framework applies more broadly. Multiple states have developed relationships with criminal hackers that allow them to maintain plausible deniability while preserving strategic capabilities.

North Korea’s state-sponsored hacking groups have long operated under various facades, shifting between criminal operations and intelligence gathering (North Korea is not Crazy, Recorded Future). Iran has similarly cultivated relationships with criminal hackers that allow for strategic deployment while maintaining distance (Iran’s Hidden Hand in Middle Eastern Networks, Google Mandiant).

Even Western democracies engage in versions of this practice, though with greater legal constraints (or not, given the lastest USA’s DOGE development). The institutionalization of offensive cybersecurity training (via university programs, military cyber commands, and public-private partnership) represents a formalized effort to cultivate state-aligned expertise while maintaining legal accountability.

Strategic Implications for Cybersecurity

For cybersecurity professionals, the Criminal Infrastructure Preservation Model demands a fundamental reassessment of how we interpret threat intelligence and respond to ransomware threats.

First, we must recognize that apparent declines in ransomware activity following enforcement actions may represent strategic pauses rather than enduring victories. The infrastructure isn’t eliminated but preserved, often returning in evolved forms when diplomatic conditions change.

Second, attribution becomes more complex when we understand the deliberate engineering of deniability. The question isn’t simply “is this group state-sponsored?” but “under what conditions might state control be exercised over this group?“

Third, defensive strategies must account for the strategic logic governing these attacks. When ransomware groups suddenly shift targeting patterns or operational tempo, these changes may reflect diplomatic signaling rather than criminal opportunism.

This requires reimagining deterrence strategies beyond traditional prosecution. As the provided analysis suggests, each arrest may paradoxically enhance state control rather than diminish it. Effective deterrence must target the infrastructure preservation mechanisms themselves – disrupting the capacity to maintain capabilities during apparent crackdowns.

Criminal Infrastructure Preservation in the Future

As digital infrastructure becomes increasingly critical to national power, we can expect controlled oscillation to become more sophisticated and prevalent.

This evolution will likely include:

- More Sophisticated Preservation Mechanisms: As detection improves, the mechanisms for preserving criminal infrastructure during apparent crackdowns will become more subtle.

- Multi-Level Signaling: States will develop more nuanced methods of demonstrating control while maintaining deniability, potentially including competing ransomware groups that appear to target each other.

- Formalized Resource Convertibility: The conversion between criminal infrastructure and diplomatic leverage will become more systematized, with clearer protocols for activation and deactivation.

- Regulatory Arbitrage: International differences in cyber regulations will be increasingly exploited to preserve infrastructure while demonstrating compliance.

The ransomware operators of 2026 won’t be technically different from those of 2023— but they’ll be operating within more complex relationships with state power.

The Permanence of the Temporary

Like Shelley’s Ozymandias, whose broken statue bears the ironic inscription “Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!“, traditional ransomware analysis has focused on the visible ruins (arrest announcements, legal changes, statistical fluctuations) while missing the enduring power structures may they represent.

The apparent contradiction of ransomware’s simultaneous expansion and decline resolves when we understand it not as a purely criminal phenomenon but as an application of the Criminal Infrastructure Preservation Model: a mechanism through which states demonstrate control over digital activities within their borders while preserving valuable capabilities for strategic deployment.

This framework explain the puzzling patterns observed throughout 2024 and early 2025; and it provides a predictive model for anticipating how these dynamics will evolve as digital infrastructure becomes increasingly central to national power and international relations.

The true challenge for security professionals isn’t celebrating ransomware’s supposed decline but understanding how its formidable capabilities are being preserved and redirected within an increasingly sophisticated system of state power projection in cyberspace.