False flag operations in cyberspace are more than funky tactical attempts at simplistic deception; they are calculated moves within a broader strategic framework.

Advanced adversaries may employ overtly flawed disguises not because they expect them to be effective indefinitely, but because they understand the complexities, the pains and the time it takes for defenders to unravel the truth.

This deliberate use of easily discoverable false flags can create initial confusion, delay response efforts, and exploit the procedural and bureaucratic inertia that often hampers incident response teams.

Moreover, the psychological impact of uncertainty can erode trust in attribution findings, which adversaries leverage to their advantage.

But those are just the tip of the iceberg.

Turla Did It Again: Pwning APT’s Offensive Infrastructure

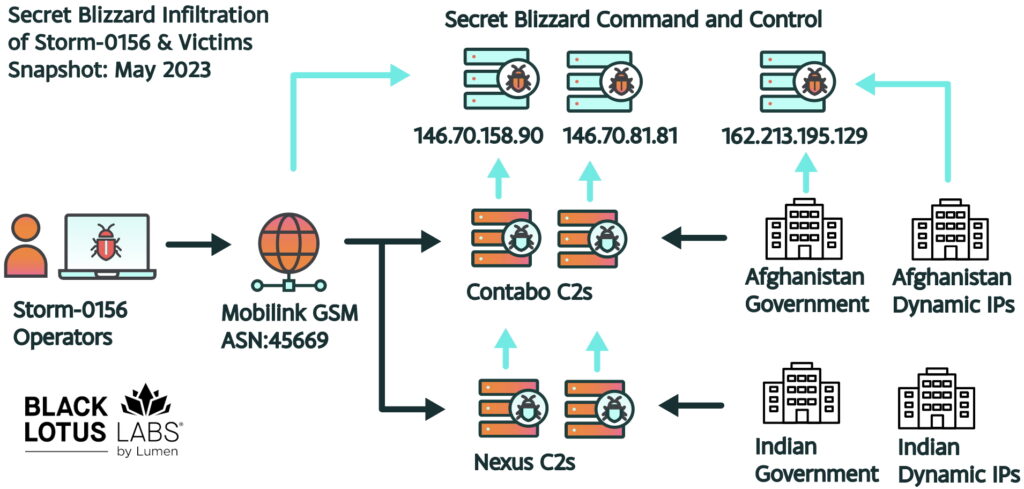

Recent revelations have shed light on a sophisticated campaign orchestrated by the Russian-based threat actor known as Turla, (a.k.a. Secret Blizzard, Venomous Bear, Uroburos, …). Lumen’s Black Lotus Labs uncovered that Turla successfully infiltrated 33 command-and-control (C2) nodes used by the Pakistani-based actor Transparent Tribe, also known as SideCopy or Storm-0156. This campaign spanned over two years.

This tactic is reminiscent of Turla’s previous activities involving the exploitation of Iranian APT infrastructure, (APT34 / Helix Kitten) as reported in 2019 by the UK’s National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) and the US National Security Agency (NSA). In that instance, Turla repurposed Iranian tools—Neuron and Nautilus—to further their own intelligence objectives. They managed to compromise Iranian command-and-control infrastructure, gaining unprecedented insight into the tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) of the Iranian APT group.

Furthermore, Turla’s strategy aligns with scenarios described by Brian Bartholomew and Juan Andrés Guerrero-Saade in their paper, “Wave Your False Flags! Deception Tactics Muddying Attribution in Targeted Attacks.” They detailed an incident where Turla, upon realizing they were about to be discovered by an incident response team within a European victim’s network, deployed a second-stage Chinese malware known as Quarian. By uninstalling their original Wipbot malware and leaving Quarian behind, they effectively misled investigators into attributing the attack to a Chinese APT group.

Quarian is a private malware not easily obtainable, suggesting that Turla may have access to rare tools from other threat actors. This raises the question: Are there more APT compromises by Turla that we are not aware of? The sophistication required to intrude and persist within another APT’s infrastructure indicates a high level of operational capability. Yet, the fact that these actions are eventually uncovered cloud suggests that even advanced false flag tactics may be destined to fail on the long run.

The deliberate or opportunistic infiltration of another APT’s infrastructure represents a significant escalation in cyber espionage tactics. It not only grants access to valuable intelligence collected by the compromised group but also provides a strategic vantage point to monitor their operations in real-time. This approach underscores the global trend of cyber espionage from direct attacks on target networks to more indirect methods, including the ones that exploit the operational capabilities of other threat actors.

False Flag, Attribution, and Threat Intelligence

The concept of the false flag has deep historical roots, originating from naval warfare where ships flew flags of other nations to deceive enemies. In the context of international humanitarian law, such deceptive practices are forbidden due to the potential for escalating conflicts and violating principles of fair conduct. However, in the realm of cyber operations—often shrouded in secrecy and lacking clear international regulations—advanced persistent threats (APTs) may take liberties with these norms, engaging in covert activities that blur the lines of attribution.

In cyber threat intelligence, the challenge of attribution is multifaceted and complex. False flag operations add a significant layer of obfuscation, deliberately manipulating forensic evidence to mislead analysts and investigators. “Wave Your False Flags! Deception Tactics Muddying Attribution in Targeted Attacks,” delves into this phenomenon extensively. They argue that while attribution remains a critical aspect of threat intelligence, the process is fraught with uncertainties and risks, especially when adversaries intentionally plant misleading indicators.

Attackers are increasingly aware of the weight that attribution carries in the geopolitical landscape. They may purposefully craft their operations to exploit this, creating “tertiary effects” by provoking misguided responses based on faulty attribution. This manipulation can lead to diplomatic tensions or unwarranted retaliatory actions, underscoring the hefty cost of misattribution. Reliance on traditional attributory indicators—such as IP addresses, malware signatures, or language artifacts—can be perilous when adversaries actively engage in deception.

Attribution in cyber attacks is often dissected into multiple levels, ranging from the technical specifics of malware to the identification of individual actors and state sponsors. A defending organization must consider the appropriate level of attribution necessary for its purposes. For instance:

- Malware Level: Malware Level: Linking a malicious sample to a known malware family to understand its capabilities and develop stronger detection mechanisms.

- Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTPs): Analyzing the attacker’s methods to hunt for unseen pattern and enhance behavioral defenses.

- Campaign Level: Linking multiple incidents to a single operation or campaign, providing context about the scale, targets, and intentions behind the attacks.

- Threat Actor Level: Identifying the group behind the attack to assess motivations and threat capabilities.

- Sponsor Level: Determining the state or organization sponsoring the threat actor to understand ecosystem-level implications.

- Individual Identity Level: Attributing the attack to specific individuals for legal action, accountability or dissuasion.

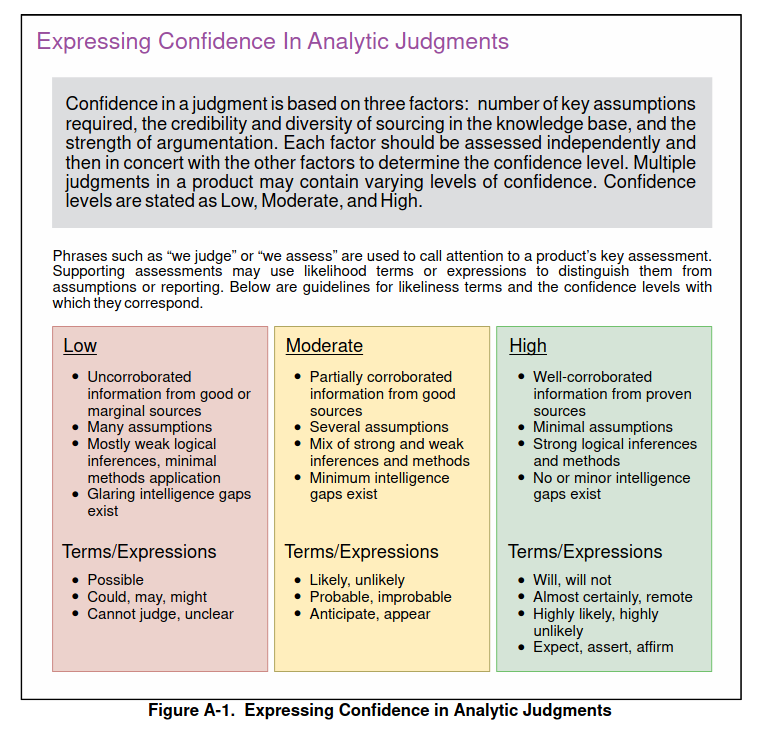

The necessity and utility of attribution vary depending on the defender’s objectives and mandates. As Guerrero-Saade and Bartholomew note, the value of attribution must be weighed against the risks of misattribution. They emphasize the importance of estimative language and cautious interpretation, advocating for transparency about the confidence levels in attribution assessments.

Fostering collaboration among international intelligence and cybersecurity communities enhances the collective ability to detect and attribute sophisticated false flag operations. Sharing intelligence, methodologies, and insights helps bridge gaps that individual organizations might miss. Such cooperation is crucial, especially when facing adversaries that operate across borders and employ advanced deception tactics.

Ultimately, understanding the motivations and capabilities of threat actors is crucial in accurately attributing attacks and responding effectively. The pursuit of attribution should be approached with rigor, skepticism, and a recognition of its limitations. Reliance on technical indicators alone is insufficient. A holistic approach that integrates contextual intelligence—including geopolitical motivations, historical behavior patterns, and strategic interests—is essential.

A Bear with Shoes Still Walks Like a Bear

Adversaries may adopt tools or indicators that suggest another group’s involvement, but their operational behaviors often betray their true identities. Even when using another group’s malware or infrastructure, threat actors continue to exhibit patterns consistent with their training and operational mandates. False flags may serve as temporary tactical moves to delay incident response, instill confusion, or even troll the target—as seen with Lazarus Group adopting the “Guardians of Peace” persona during the 2014 attack on Sony Pictures, or APT28 masquerading as the “CyberCaliphate” during the TV5Monde cyberattack- or an operational step in an hybrid campaign (APT28 and the emails leaked by the personna Guccifer 2.0 as a whistleblower during the 2016 DNC hack).

Operational tradecraft leaves subtle yet discernible traces. Factors such as operational timing, target selection or counter measures adaptation often reflect the underlying methodologies, and sometimes organizational type, of the true actor. By focusing on these operational fingerprints, analysts can peel back layers of deception: meta-espionage. Gaining strategic advantages by infiltrating the operations of other threat actors.

By compromising another APT’s infrastructure, adversaries like Turla are not just masquerading their activities. The fact is, even with Iranian Neuron and nautilus malware or Transparent Tribe’s toolset, they were ultimatly discovered. But are moreover accessing the collected intelligence, tools, and operational insights of their competitors or even allies. This grants them a multi-dimensional advantage:

- Access to Unique Intelligence: Acquire intelligence that might be difficult or impossible to obtain through direct targeting, including sensitive data already collected by the compromised group.

- Understanding Competitors’ Capabilities: Assess the tools, techniques, and procedures of their peers or rivals, enabling them to anticipate future operations and develop countermeasures.

- Manipulation: Manipulate or sabotage adversaries’ activities, redirect attacks, or feed disinformation, impacting the quality of derived intelligence or the covered operation.

- Pragmatism: Leveraging existing infiltrations or leaks reduces the need to expend resources on initial compromises, allowing one to focus on higher-level objectives.

- Plausible Deniability and Extended Deception: Operating through another APT’s infrastructure adds layers to their deception, complicating attribution efforts and increasing the likelihood that any detected activity will be misattributed.

This reflects an universal truth in espionage and clandestine operation where the lines between adversaries, competitors, and allies become blurred.

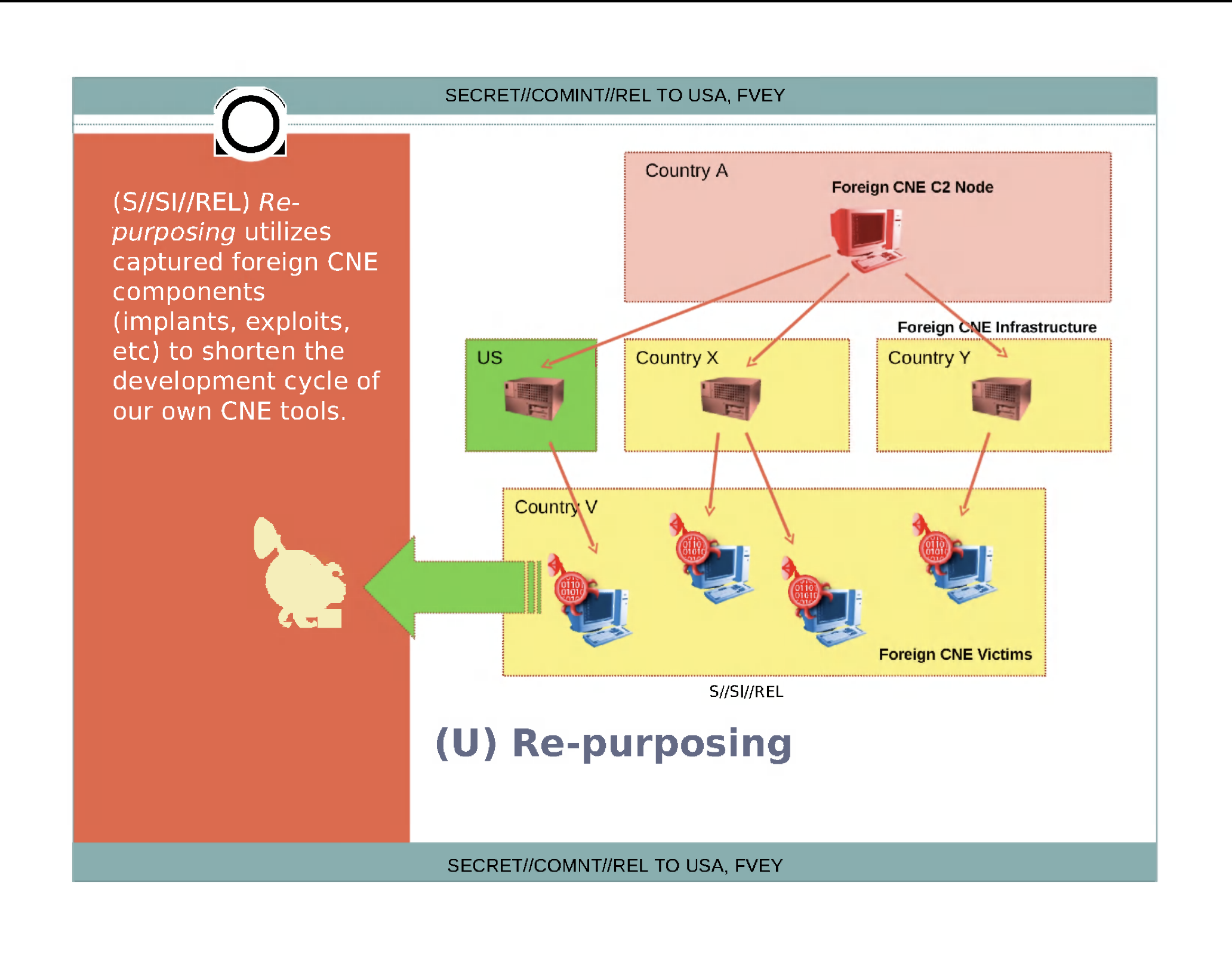

Beyond False Flag: Fourth Party Collection

The concept of Fourth Party Collection, as revealed in leaked NSA documents by Edward Snowden, titled ‘4th Party Collection: Taking Advantage of Non-Partner Computer Network Exploitation Activity‘ refers to the practice of exploiting other actors’ cyber espionage operations to collect intelligence indirectly. In a slide titled “I Drink Your Milkshake,” the NSA detailed how they leveraged non-partner computer network exploitation activities to their advantage. By infiltrating or wiring the operations of other intelligence services, they could siphon off data and offensive tools without deploying their own exploits extensively.

By compromising another intelligence system’s operations, an actor can gain access to both the collected data and insights into the adversary’s intelligence priorities, methodologies, and capabilities. This dual benefit amplifies the value of such operations. However, it also introduces ethical and legal complexities, particularly when non-adversarial entities are involved. For defenders of sensitive organizations, this underscores the necessity of robust security practices even within trusted networks, as the compromise of one ally could cascade into broader compromission. Trust relationships must be scrutinized, and mutual security standards must be established.

Moreover, by embedding themselves within the operations of other threat actors, sophisticated adversaries can subtly influence or even control the actions of those groups, steering them toward targets of their own choosing or away from sensitive areas. This level of strategic manipulation transcends traditional espionage, entering the realm of proxy warfare: If a state actor can manipulate another APT group into attacking specific targets, they can achieve their objectives while maintaining plausible deniability. Moreover, they can provoke conflicts between other nations, sowing discord and diverting attention from their own activities.

But the risk is that Fourth Party Collection can lead to the contamination of intelligence sources. Data obtained through such means may be tainted, intentionally manipulated, or incomplete, leading to flawed analyses and potentially disastrous decisions based on faulty intelligence. This possibility challenges the integrity of the global intelligence cycle and necessitates to not overly trust one collection method over all the others.

This type of meta-espionnage complicates attribution. But more importantly it introduces cyber-espionnage to the global dimension of the world nations chessboard of manipulation and influence.

Adversaries Have Their Own Threat Exposure

The Turla operation against Transparent Tribe or APT 34 underscores that even sophisticated threat actors are not immune to being targeted themselves. This dynamic is not unique to the cyber realm; in both the criminal world and intelligence communities, entities often engage in counter-intelligence activities to monitor, learn from, and potentially disrupt the operations of others.

The reality that threat actors operate in a contested environment has significant implications for how we perceive the threat landscape. Attackers must allocate resources not only toward offensive capabilities but also toward securing their own operations against intrusion. This creates opportunities for defenders, law enforcement and intelligence agencies to exploit potential weaknesses in adversaries’ operationnal postures.

When threat actors become targets themselves, it creates a complex ecosystem where attackers and defenders share overlapping objectives and vulnerabilities. When attackers must defend their own infrastructure against sophisticated intrusion from other threat actors, they engage in behaviors traditionally associated with defenders. This convergence creates opportunities for defenders and intelligence agencies to exploit these overlaps. The knowledge that adversaries are preoccupied with defending against peers introduces operational strain and resource diversion. Threat actors must allocate finite resources to both offensive campaigns and the security of their own systems.

By uncovering and analyzing what the adversaries try so desperately to protect, it gives a unique perspective about how they perceive their own flaws. Maybe it is something that they don’t want anyone to know about; maybe it is an inherent, hence unchangeable, part of their operational architecture. Anyhow, disrupting those parts, sharing them with peers, or even publicly revealing those counterintelligence insights may have a deeper effect on the adversaries’ operational posture than putting their IOCs in a threat intelligence database.

Yet, disclosing detailed knowledge about adversary vulnerabilities could expose defenders own methods and sources, potentially compromising ongoing investigations or intelligence capabilities. Public exposure might also provoke adversaries to retaliate or escalate their activities, possibly leading to unintended consequences.

The Impact of Fourth Party Collection on Cyber Attack Impact Assessment

For defenders and victims, the question arises: “Why do we care who is behind the attack?” In scenarios of multi-layered intrusions, the impact assessment can vary significantly based on the identity and objectives of each actor.

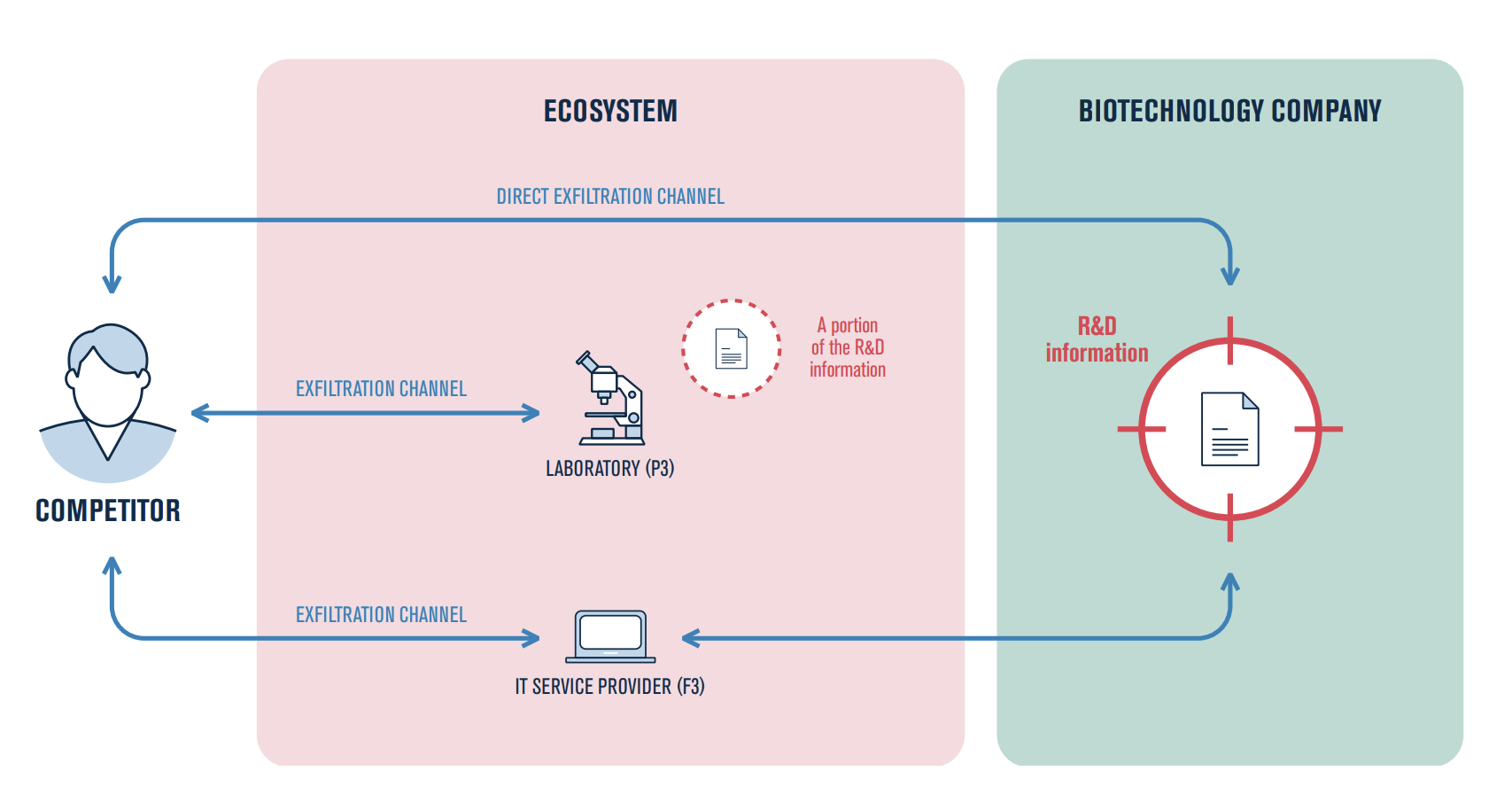

Consider a situation where data stolen by Transparent Tribe is subsequently acquired by Turla. The victim may be unaware that their information has fallen into additional hands, potentially with different intentions and capabilities. For government entities, sensitive NGOs, or critical industry sectors, understanding who possesses their data is crucial. The potential risks and consequences differ greatly depending on whether the data is held by a group of script kiddies or a global intelligence agency.

The chain of custody of compromised data drives the strategic response and risk mitigations. Different threat actors may target distinct types of information or exploit the data in varied ways—ranging from direct exploitation to leveraging it for further attacks or disinformation campaigns. Therefore, accurate attribution and understanding the adversary’s intent become integral to effective incident response, legal considerations, and diplomatic actions.

In light of these challenges, organizations must enhance their incident response frameworks to account for the possibility of multi-layered threats.

Conclusion

Cyber espionage is fraught with deception, misdirection, and strategic exploitation. On both side. Despite efforts to conceal their true identities, adversaries inevitably exhibit operational behaviors that can betray them. By infiltrating other APT groups’ infrastructures, actors like Turla or NSA TAO gain access to valuable intelligence and tools, complicating attribution and challenging traditional responses.

The involvement of multiple threat actors exploiting one another’s operations introduces significant complexities in impact assessment and incident response. Understanding who possesses compromised data is crucial, as different actors may exploit the information in varied and potentially more harmful ways. Accurate attribution and insight into adversaries’ intentions are essential for effective risk mitigation, legal considerations, and strategic decision-making.

Recognizing that adversaries themselves are vulnerable opens opportunities for defenders to disrupt their operations by targeting the aspects they most strive to protect. The ability to anticipate and counter sophisticated deception tactics becomes paramount. By focusing on adversaries’ inherent vulnerabilities and operational flaws, defenders can develop more effective strategies that have a deeper impact than traditional defensive measures. Embracing a multidimensional approach to cybersecurity, which includes technical analysis and strategic intelligence, is vital for navigating the evolving challenges posed by advanced cyber threats.